Is Minimum Volatility Investing becoming more risky?

With the dramatic market losses of the Global Financial Crisis still so fresh in investors’ minds and because of the length of the market’s upward movement since then, investors have felt a growing desire to protect assets. This sentiment has been prominent in the fixed income market, and we believe we are seeing similar signs in the equity markets. Pricing within the market can have a profound significance at times, and, as a result of this trend, we believe something meaningful is happening in the pricing of “safer” assets, also known as minimum volatility investing.

In our 2Q16 commentary, we remarked on our discomfort at witnessing a large percentage of the world’s sovereign debt trading at negative rates, and therefore at high prices, given the inverse relationship of debt price to interest rates. This debt recently hit $13.4 trillion. We discussed our concern that this behavior would yield poor results as it became obvious that investors were using a “greater fool” mentality: paying an uneconomical price for an asset in the hopes that someone will pay more for the same asset later. We have noticed indicators that this mentality is beginning to take hold within a portion of the equity market as well.

In particular, we are focusing our attention on an equity group that has been classified as having more “protection,” because it has historically exhibited smaller losses and less volatility than the overall market when uncertainty grips world markets.

There is ample research suggesting that owning a basket of stocks that exhibit lower volatility can achieve better returns over long periods of time at relatively low levels of risk. This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that investments that typically reside in this category are mature, boring, and considered to have suspect growth potential, all of which prevent exuberance and volatility. Until recently, the “low vol” strategy was more prominent in the institutional space, given the rather sophisticated portfolio construction techniques required for its execution. However, this has changed with the introduction and adoption of low or minimum volatility investment vehicles. However, we fear that the newfound attention may be leading to a false sense of security.

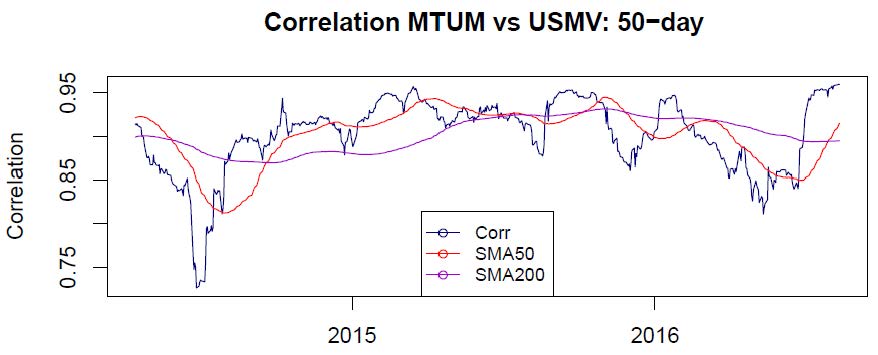

The problem we see is that, as a basket of low-volatility stocks turns into the ‘it’ group, it begins to exhibit strong price momentum. This momentum is best expressed by the increasing correlation of the minimum volatility ETF (USMV) to the momentum factor ETF (MTUM). This momentum has driven the group’s pricing to levels that are far from defensive. As reported by Jason Zwieg of the Wall Street Journal, the group is now trading at price-to-earnings valuations 10% greater than the overall market. BlackRock calculates the price-to-book multiple of the minimum volatility ETF (USMV) to be 25% greater than that of the overall market.

The riskiness of momentum is that, though it feels good, it takes on a life of its own and can beget more momentum, leaving fundamentals forgotten. As we discussed last year in our newsletter (A Momentous Mistake? – May 2015), momentum can have a long tail, but when it changes, it can swiftly lead to material losses; corrections happen fast and floors are often much lower than they are perceived to be. The common analogy used in investing to explain this is a crowded theater: The owner of a theater loves when the seats are filled, and all those attending take comfort in the belief that they are in good company, as most or all of the seats around them are filled. However, if and when the fire alarm rings, the four exits become very small relative to the level of demand to leave the theater.

The sheer number of investors gravitating towards this concept of baskets of low-volatility stocks and the elevated valuation of these baskets lead us to believe that the historical factors that have allowed for lower volatility and defensibility may not be present when markets weaken. Markets are swung by the changing attitudes of participants, potentially oscillating quickly between greed and fear. That change is most prominent in areas of the market where greed has been focused. We see minimum volatility strategies as the potential epicenter for the next correction, since they have been rendered unpredictable by investors’ blind faith.

All of this reinforces the philosophy in which we believe and process we have built. The only safe asset in times of significant duress has been cash. Therefore, if and when the warning signs appear, we will look to cash as a haven, not a potential epicenter.