“Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms one’s preexisting beliefs or hypotheses while giving disproportionately less consideration to alternative possibilities.” – Wikipedia

The S&P 500 index, a proxy for the US equity market, has risen 6% in the first ten weeks of 2017 and almost 30% from the February lows one year ago. Throughout the run-up, investment pundits have expressed concern that the market was richly valued, citing the historical highs in one measure of equity market valuation.

There are ample reasons to be cautious, but valuation is not high on the list. The increasing tensions between the US and its largest trading partners are suboptimal, to say the least. The rising fear of inflation and the uneven global interest rate environment adds a level of uncertainty to the normalization process. Political friction in Europe is increasing the probability that the economic union we have known for the past two decades—the European Union—may be cracking beyond repair. Asia, for some, may be a bright spot, but it is not without its concerns: China appears unable to control North Korea and the Philippines.

We have discussed in prior letters the high level of uncertainty—elevated since the 2008 financial crisis—that has been expressed by commentators. For the past 8 years, the fear centered on banking system instability, weak economic growth, and lack of corporate investment. Now top concerns are political in nature. Interestingly, we have seen corporate leaders become more optimistic and more willing to invest while the world’s political leaders appear to favor retrenchment.

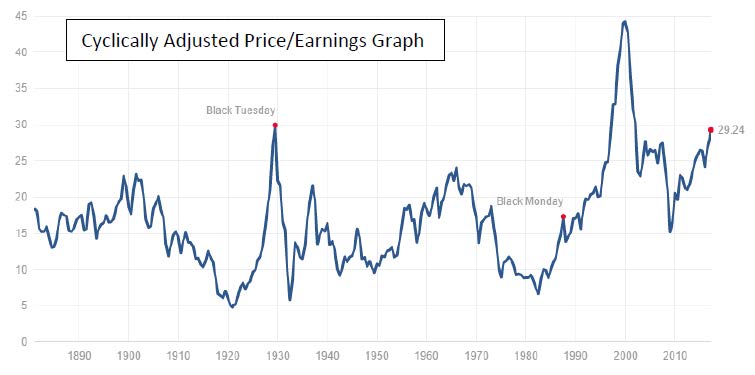

This brings us to the idea that markets movement to date has been fairly rational. Valuation is repeatedly used as a warning sign, and it has become common to reference a graph showing the current market at a historically high valuation level. To demonstrate this point, many focus on the Shiller CAPE ratio,[i] which looks at the cyclically-adjusted prior 10 year average earnings against the current value of the market.

However, examining one backward-looking signal that has deemed the market “overvalued” for 416 of the past 422 months is not a sensible approach to determining extreme valuation. Many experts have pointed out obvious flaws with this measure, yet it is continually used to support a cautious view—a key sign of confirmation bias.

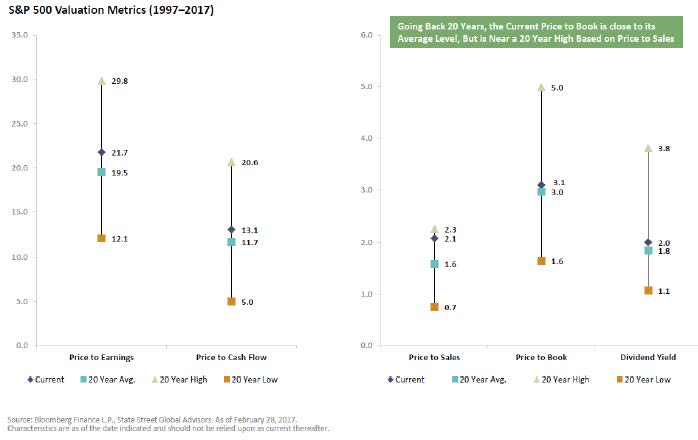

Other valuation signals are not nearly as bearish as the Shiller P/E Ratio, nor do they foster the same fears. From an analysis of several other measures, the US equity markets are looking only slightly above historical averages. Again, we caution on using any measures in isolation as the risk-on bias can increase.

One of the largest risks of relying on the Shiller CAPE ratio for a view on valuation is the mismatch between a forward-looking price and backwards-looking earnings numbers. By making this statement, we are likely to elicit the dreaded response, “It’s different this time.” This is neither our intent nor a fair response. We base our beliefs on sound reasoning built off of empirical evidence. Because the indicator has a weak track record, we feel justified in questioning its implications.

To look backward, a person must sacrifice his or her forward-facing view. As we mentioned above, there are several risks that remain in front of us, but we need to acknowledge the positives as well.

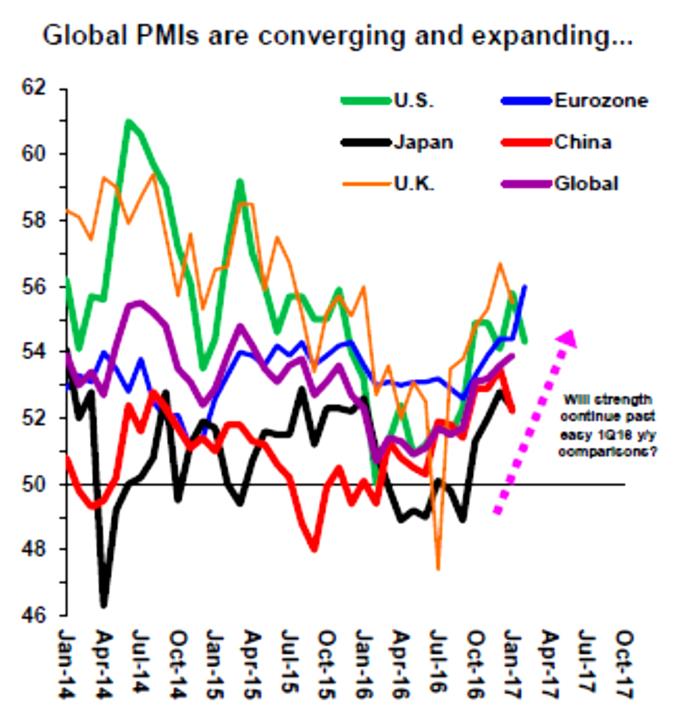

Coordinated Global Economic Growth

Globally, economic activity is picking up. For much of the last three years, the major world economies have been experiencing rolling softness. Europe went through it in 2012, Asia was hit in 2014 and 2015, and the US felt a near-contractionary period in 2016, instigated by the rapid deterioration in oil production. This contraction appears to be ending. All regions are experiencing higher levels of economic activity, and expectations are optimistic.

The re-emergence of US production activity may be followed quickly by an increase in economic activity brought about by millennials.

A Demographic Wave

Many fail to recognize the large economic impact brought about by aging generations. In its simplest form, economic activity is a product of the population and people’s consumption habits. Since the turn of the century, the US has been burdened by the small size of the GenX’ers relative to the Baby Boomers. As in any generational shift, it is up to the next generation to match and build off the prior. Because GenX was materially smaller than the Baby Boomer generation, the economy suffered lower collective spending power.

Demographics are about to become very economically productive. Millennials, the echo boom, are 15% larger than GenX. They became the largest segment of the labor force in the first quarter of 2015 and are now increasingly entering the higher spending segment of their life as they buy their first houses and have their first children.

A Changing Political Landscape

Despite the fear that envelopes our political landscape, there are likely to be future pro-business outcomes that benefit corporate earnings, the economy, and the markets. Although it is difficult to forecast timing, the pro-growth efforts mentioned to date would have a material economic positive impact. Corporate tax rate reduction has been estimated to boost earnings by 10-12%, which is not included in current assumptions. Though the immediate impact of increased earnings is material, it is the longer-term impact on global competitiveness that drives an enduring growth picture. Our conversations with CEOs of companies of various sizes over the past 25 years have strengthened our belief that a corporate tax rate in line with other major economies and a more reasoned approach to regulations would allow firms to refocus on the US as a source of production. Many forget that the US can be a low-cost producer, given the large and inexpensive natural resources available. Add to that the potential to repatriate some of the $2.5T held off-shore and the growth forecasts for the US could meaningfully adjust up.

Our intent is not to elicit a euphoric response from the reader. Our goal is to point out that looking only for those data points that confirm an intended bias will likely lead to a wrong view of the world. We have built our processes to rely on empirically proven concepts and to remove many of the biases that continue to plague the markets. The Auour strategies currently stand in moderate risk regime, favoring high quality, developed market securities with a small amount of cash to take advantage of any near term volatility.

[i] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyclically_adjusted_price-to-earnings_ratio

[ii] Jeremy Siegel at Inside ETFs Conference, January 2017. The timeframe referenced was from 1981 though 2015.