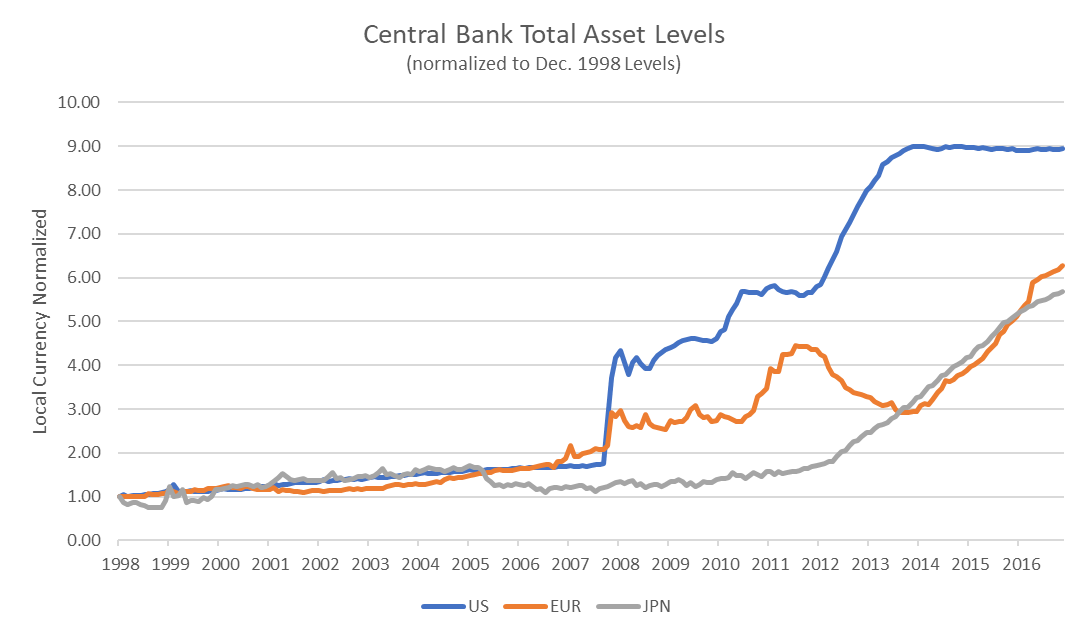

It comes as no surprise to anyone that we are sitting atop a long bull market. About nine years ago, global central banks thought it wise to fight the threat of deflation by lowering interest rates. They did this through large purchases of their respective government’s debt, competing with private investors and building up their fixed income holdings to levels not seen in modern times.

The theory by many academics (and those pushing the buy buttons) was their actions would push private investors to move more of their investments from the safety of government bonds to growth focused investments. The anticipated increase in private-sector growth investments would lead to increased economic activity, reduced economic slack, increased inflation, and higher personal income.

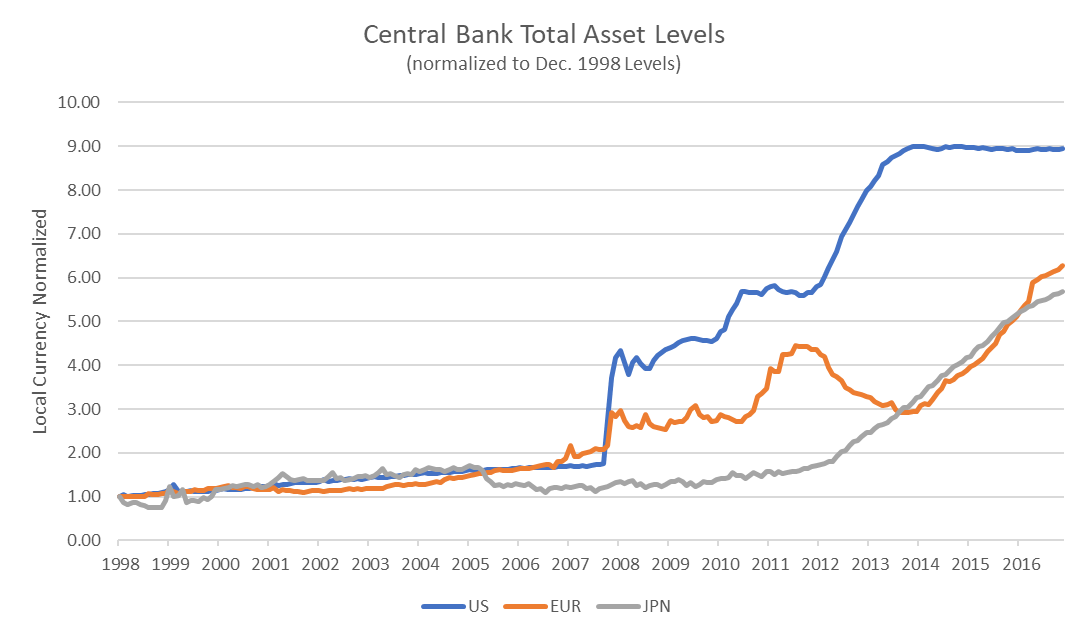

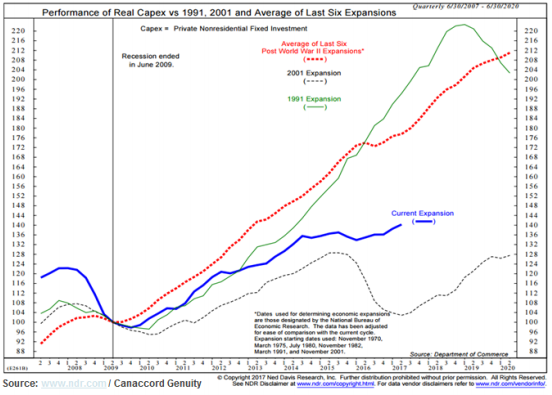

From one perspective, the central bankers can pat themselves on the back as we are seeing capital expenditures and plans for future spending increase.

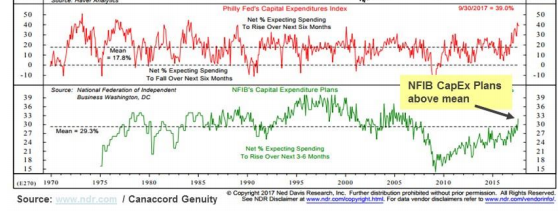

But, when viewed from a historical context (below), it is much less impressive. (The current cycle is represented by the blue line and the average of the last six expansions since WWII is represented by the red line). Real capital investment has been anemic since the Great Financial Crisis and barely better than the post-2000 cycle (again, another cycle when the Federal Reserve worked aggressively to push rates lower).

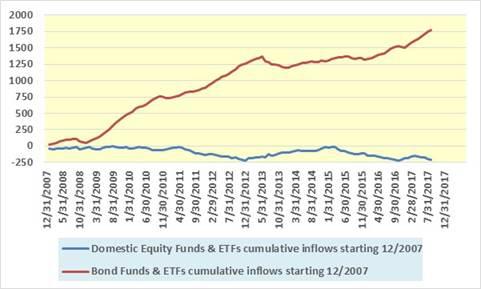

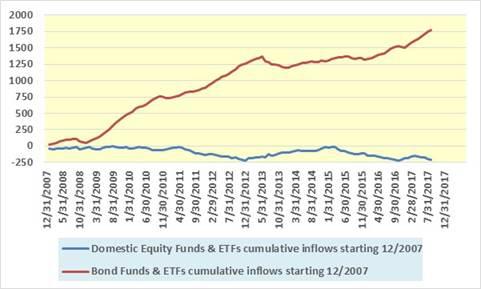

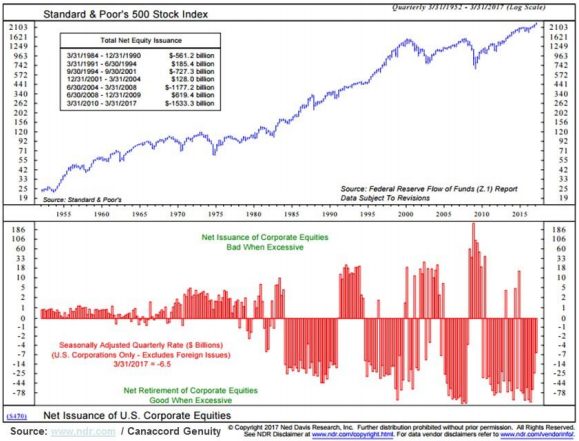

The combination of a large amount of money being pushed into the financial system combined with lackluster capital expenditures has many fearing the benefactor has been financial assets. It does not take much to speculate that the easy money environment has resulted primarily in financial asset inflation. Though that may be true for bonds, it would be hard to argue the money found itself piling up in equities as money continues to move out of the domestic equity markets.

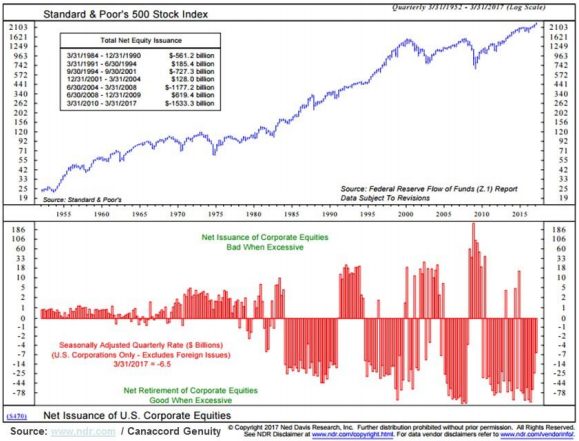

Rather consistently over the past 20 years, we have seen companies reduce the number of shares outstanding through corporate buybacks. There is little doubt that a low interest rate environment has aided this behavior but with corporate profitability near all-time highs and balance sheets healthy, it would be difficult to argue this environment as precarious.

Where we have heightened scrutiny is in the various bond markets. Similar to the game of Jenga, the strategy of pulling a piece from the lower levels (in this case, sovereign bonds once considered risk-free assets) and placing them on top of the increasingly unstable tower (high yield bonds, municipals, emerging market bonds, etc) leads to increased instability.

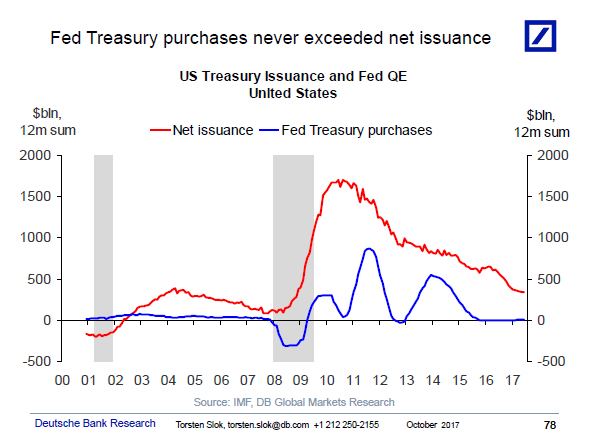

And that is what we currently fear the most. The US Federal Reserve stopped adding to their balance sheet 3 years ago and has raised rates 3 times (soon to be four). They have now announced plans to start the liquidation process, ever so slowly. Markets have been nervous that the act of taking dollars out of the system would result in a Jenga-like quake. To date, it has not.

Deutsche Bank offers a graph that, to us, offers an explanation why the Fed’s unwind has not caused a ripple through the system. Though the Fed’s purchases and manipulation of the government bond market has been large (they currently own $2.5 trillion in Treasury securities, roughly 15% of total outstanding Treasury bonds), their purchases have not been larger than the net issuance of new debt. In other words, they have been a large player in the market but have not “become” the market.

So now, you pulled the next piece from Jenga and it didn’t fall. Take a breadth and relax. On to the next player…

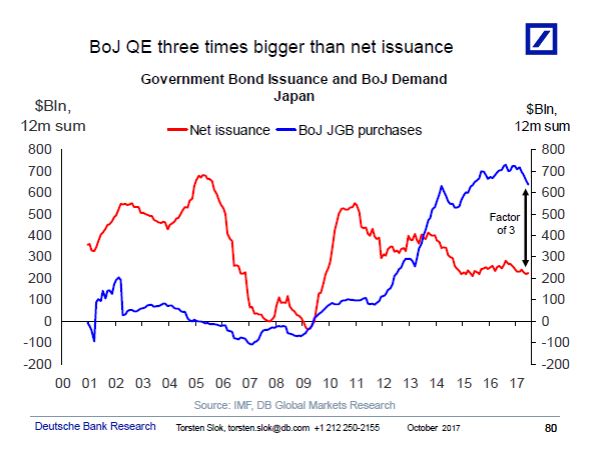

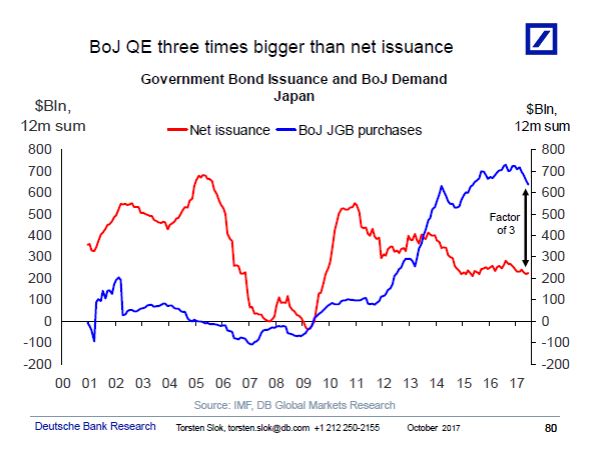

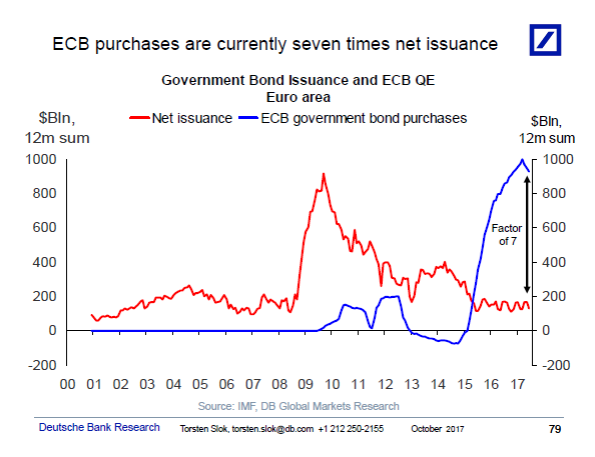

The US is not playing this game alone. At least two others are at the table and they may not exhibit Mrs. Yellen’s steady hand. Deutsche Bank has created two more graphs that look at the same data, but for Europe and Japan. As depicted below, Europe and Japan may be playing a little more aggressively. In both cases and unlike the US Federal Reserve, they have been buying not just newly issued government debt but also already created debt. And to make matters worse, the European central banks have had to buy corporate debt as the supply of available government debt has dwindled.

Imaging a game of Jenga where all the lower base has been reduced to a level where no more opportunities exist, so you are driven to start pulling higher up the stack. How often does the game continue with little risk?

Japan may be even further into the game as their central bank has been a major buyer of Japanese equities. Recent data suggests the Bank of Japan owns approximately 60% of all issued Exchange Traded Funds existing within the country.

We are depicting the financial situation as precarious. We are watching these build ups of instability and see paths where they can be handled with little enduring issues for most private investors. The US private sector is looking healthy and most believe that corporate America can withstand (and may even benefit from) higher interest rates. Europe and Japan may have stable hands, too, and produce an outcome that is not dramatic. Time will tell. As always, we continue looking for signals that indicate the severity and duration of any potential disruption.