“The real hero is always a hero by mistake; he dreams of being an honest coward like everybody else.”

—Umberto Eco

False Heroes

Just a note: We have been quiet for the past two months not because we lacked things to say but because we felt everyone needed a break. We can’t be the only ones fatigued by the daily feed of dire narratives based on selective data. Rather than try to speak through the noise, we decided that reading, reflection and a little more reading was the better path. After that pause, it’s time to get back at it—and in front of what will likely be an eventful end of the year.

One more note: We are tired of the word “unprecedented” and think it a lazy way to view current events. Pandemics have occurred in the past. Recessions aren’t new. Politics have been this bad before. In other words, the world has seen worse scenarios, so to say this period is unprecedented is false. It also disrespects the trials and tribulations our ancestors experienced. OK, enough ranting. Back to previous programming.

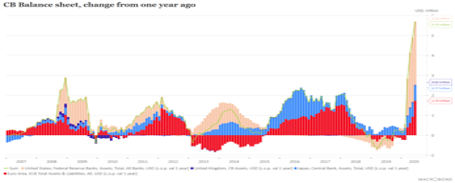

We ended 2019 and began 2020 with a party analogy. We likened our move to increasingly high levels of cash in late 2019 to getting our coats and leaving the party before it got out of hand. In February and March, the spreading pandemic and government lockdowns abruptly stopped the party. The global lockdown was a blunt object used on the complex and fine texture of our economy. The hangover looked to be a doozie, but the U.S. Federal Reserve (also known as the lender of last resort) came to the rescue. (Our hero!) By the end of March, they promised to support the economy in every way possible—lowering rates; buying government, corporate, and municipal debt; even offering direct loans to businesses—thereby pushing liquidity into every pocket of the economy. In other words, they ramped up an after-party, with a refreshed band and bubbly flowing from the fountains.

The Federal Reserve’s efforts were no different than those taken by the central banks of other countries. They all promised to maintain low rates until inflation moved up past some subjective level. Though the intention was to mitigate discomfort in order to stimulate investment and economic activity, the result is not assured. And the unintended consequence might be increased instability.

The conventional thinking behind lowering rates is, and has been, that it stimulates greater investment, which leads to higher employment, which leads to greater income. And more income drives higher consumption, which heats up economic activity. The hotter economy then brings about higher prices. Once inflation picks up, central banks can raise rates to lower consumption, which brings on a modest economic contraction, which starts the cycle all over again. The central bankers, with the U.S. Federal Reserve being the leader among them, are perceived as regulating the fuel of the economy’s engine, thereby controlling the speed of its activity.

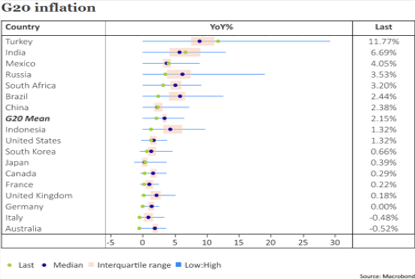

But what happens if the results of the Fed’s actions are not what they intend? Most people consider the inevitability of lower rates bringing on inflation to be firmly established. It is commonly perceived that low inflation is the result of money being “too tight.” However, when we look around at developed economies around the globe today, lowering rates has not caused inflation. Japan has negative interest rates—yet is struggling with deflation. Europe also has negative rates, yet it hasn’t come close to hitting its 2% inflation target. So, we have to ask: If it doesn’t look like a duck, doesn’t quack like a duck, maybe… it isn’t a duck?

To the minds of most central bankers and government officials, inflation is not necessarily a bad thing. Some inflation promotes the perception that wealth is growing, acting as an impulse to spend now rather than later. (To a cynic, it is just a silent tax.) However, for most of the population, inflation is not a panacea. Past episodes of higher inflation have shown a tendency to benefit the few at the expense of the many.

Seeing lower rates not lead to higher inflation has stirred up interesting discussions. Some academics increasingly believe that lower rates bring about lower inflation—a spiral with potentially material consequences. It is not hard to imagine these academics are right when you examine how inflation is calculated: The largest component of the inflation calculation is housing. Housing inflation is looked at as a change in the cost of shelter (be it either owned or rented). The calculation used to determine the growth in the cost of housing depends significantly on mortgage rates, which are tied to the interest rates set by the Federal Reserve. Lower rates lead to lower mortgage costs, which leads to lower inflation in the housing component, which makes up more than a third of the inflation measure.

The old saw that low rates stimulate economic activity also might not be true. Instead, consider that lower rates stimulate significant debt, which acts as a deflationary weight on the economy. It is not hard to see example’s in your own experience: If you borrow money for current consumption, you need to either make more or spend less to pay off that earlier debt-driven consumption. Regardless, debt needs to be paid. Borrowing now means you must pay it back later, with interest. Without an influx of more money, debt for consumption brings on deflation.

When empirical results no longer follow theory, we are proponents of going back to fundamental principles to reset our thinking, just as we pull out a compass when lost.

Economics 101

Let’s reflect on the foundational principle of economics.

At the root of economics is the relationship between supply and demand. The price of any good or service will be the fulcrum point between the effort required to supply the good and the end consumer’s demand for that good or service. In the simplest illustration, if demand is greater than supply, more people will want product than is available, the price will trend higher, and inflation will follow. If supply is greater than demand, people have more competitive options and prices trend lower, as does inflation. The balance of supply and demand is the core pricing system of the economy and defines when an economy finds equilibrium.

A well-regarded economist, Hyman Minsky, evolved the thinking of an economy’s means of finding an equilibrium by speculating that economics must be viewed as having two pricing systems, not one. He says changing interest rates brings about different outcomes within economic systems. One pricing system is for goods and services consumed now, and another pricing system is for investments and savings.

To further this thought, Randall Wray, a professor of economics that studied under Minsky, writes, “Hyman Minsky’s financial theory of investment rests on a bifurcation of an economy’s price systems. On the one hand, there’s the price system for goods and services. And inflation here is what central banks look to hold in check. But at the same time, there is a wholly separate price system for assets. And it’s here where stability leads to asset price inflation, a buildup in debt, instability, and, eventually, crisis.”

If we believe these two pricing systems to be foundational, we can then explain our current and seemingly contradictory environment, in which lower rates have simultaneously produced lower inflation and higher asset prices.

Price System One: Goods and Services

Let’s look at inflation first. No surprises here. Lower rates on debt financings have allowed more companies to fund investments that drive up productivity (i.e., produce more goods at the same or lower cost, which is deflationary), or, if you are a cynic, to stay in business despite a poor business model, which can also produce excess supply and temporary deflation. Keep in mind that one person’s debt is another’s asset. Companies’ debt is purchased by investors, with the expectation that the debt will be paid back, thereby providing a reasonably safe method of earning income on their savings.

As central banks lower interest rates in an effort to help lower the cost of funding investments and consumption, those accustomed to earning a certain level of income on their savings must now accept less income, reducing the impulse to spend (lowering demand). Excessive supply, with the same or lower demand, will result in deflation.

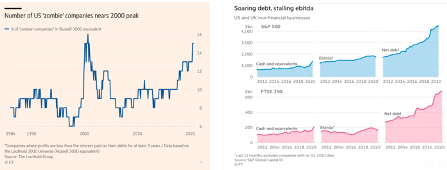

The classically expected result of lowered interest rates—increased economic activity— sounds good, but it might be driving the pricing system out of equilibrium, as shown in the charts above. The percentage of U.S. companies unable to cover the costs of servicing their debt—as assessed when we were going into the pandemic, not now—was already approaching the percentage we saw in 2000. We can assume it has grown since. Another effect of the low rates has been that companies comprising the S&P 500, or its U.K. equivalent—the ones we think of as mature and stable—have taken advantage of the low interest rates to add more debt, all while they have had little growth in profits. Therefore, much of their future profits will have to go to maintaining and paying off this debt rather than to further investments and growth. We used to say, “People think about how much debt they can afford in the good times and how much debt they have in the bad ones.” It appears most people still think we are in the good times.

To summarize, lower rates have allowed companies to produce more goods (i.e., to increase supply) than they could have during periods of higher interest rates. Lower rates also mean investors are experiencing lower levels of income from their savings (i.e., lowering demand). High supply and low demand equate to lower prices and deflation, not inflation. And the newly added debt at the corporate level, without the corresponding increase in growth to cover it, is producing an unstable environment, as described by Minsky (and Wray).

Price System Two: Capital and Investment Assets

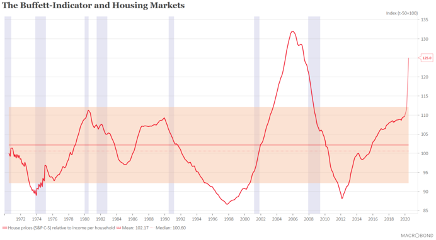

Now let’s look at the rise in the price of capital and investment assets. Increased levels of speculation are driving up the price of capital. Two types of assets, residential housing and the equity markets—both of which have leverage at their foundation—are at extreme highs. Housing within the U.S. is showing a material pick-up in prices. The pandemic has had an apparent impact on cities, rapidly driving urbanites to the suburbs.

If one believes that mortgages are debts that must be paid back, then The Buffett Indicator, which is defined as the ratio of the price of a house to the income the household makes, should be a good metric to discuss equilibrium in housing prices. When the price paid for a house is much higher than the income generated to support it, there is a good chance that you are in an unstable environment, and the purchaser is at risk of forfeiting the house, as we overwhelmingly saw in 2007 to 2010. Now may be another such time. As unemployment increases and household income falls in response, we are witnessing increasing housing prices unsupported by household income. We have not seen The Buffett Indicator this high since the housing bubble. Although the pandemic may be amplifying the effect, it was already quite high heading into 2020.

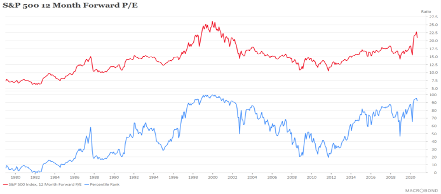

We just discussed how the largest asset of most people, their homes, have seen price increases without the income to support it. The second largest asset of most people, their investments in the public market, are also experiencing high prices not seen since the 2000 tech bubble. (Funny how that word “bubble” keeps coming up). We have always said the timing of market corrections of valuation extremes are hard to predict because the market can stay at elevated levels (or depressed levels) for a long time. However, valuation extremes are good predictors of the magnitude of pain one can expect to feel once the market moves into correction mode. At the time of this writing, the S&P 500 Index is valued (by looking at the ratio of price to forward expected earnings of the companies in the index) at a level that has only been higher than today 6% of the time during the 32-year history we track. The only time it has carried a higher value, based on earnings, was in 1999 and 2000.

In that period, we saw mass speculation within a segment of the equity markets. We are witnessing a similar level of speculation today within that same segment: technology. Most technology companies have benefited from the pandemic because established trends in online purchasing and communication accelerated during the pandemic lockdown. There is little doubt this trend will continue. And “To what end?” is not a question most speculators are asking.

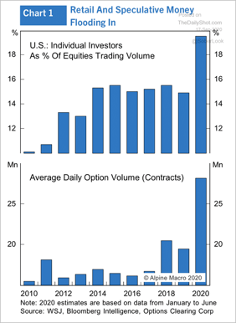

We mentioned previously that individual investors have been opening retail brokerage accounts at a rate not seen before. We are witnessing a rise in speculation by new individual investors participating in securities trading, and we see it even more in options trading. We think this is an important observation. Options are a form of leverage—you can put down less money than you have in order to participate in a larger asset transaction by borrowing. The ease of purchasing options (particularly call options) has a material influence on asset prices within the public market. As call options are purchased, the assets underlying those options need to be purchased. The purchase of options acts as an amplification to the speculation. This is another example of instability.

“Individual investors” may be the wrong term to describe the new entrants to the market. “Speculators” might be better. Because the Federal Reserve has played a role in bailing out so many, particularly during the 2008 crisis, it might have promoted a moral hazard, in that speculators might assume profits will be kept by the individual, but losses can be socialized. This has not been a solid investment strategy for individuals in the past, and we do not think it will be one now or in the future.

Conclusion

We often see central banks as heroes because they lower rates and provide ample liquidity in times of economic duress. However, in many plays, the hero turns out to be an unwitting antagonist, hubristically perpetrating a dream that keeps us from adjusting to the present. Though we do not think that central bankers are evil, their role was originally conceived of as limited. It has grown throughout time, and the effect of their actions today is not always black and white. We see them, and they might see themselves, as saviors during economic calamity. But what if they abet that calamity?

The central bank’s mandate (at least for the U.S.) originally was limited to protecting the value and stability of our currency. They were the lender-of-last-resort so citizens could trust in the future purchasing power of their savings. The central bank’s mandate expanded to include an objective of full employment for the nation, which gave them a more active role in softening economic cycles. To some, their “heroic” efforts to save us from economic cycles are, ultimately, an overreach. There’s no saving us from economic pain and postponing it can amplify it.

Adam Smith, an eighteenth-century economist and philosopher, characterized the concept of the invisible hand. As described by Investopedia, “The invisible hand is a metaphor for the unseen forces that move the free market economy. Through individual self-interest and freedom of production, as well as consumption, the best interests of society, as a whole, are fulfilled. The constant interplay of individual pressures on market supply and demand causes the natural movement of prices and the flow of trade.”

This metaphor highlights how millions of small decisions made by individuals, out of self-interest, can have the unintended effect of being a widespread benefit to society. Referring back to the beginning quote, we believe the “real” hero is the collective force of billions of people acting in alignment with logic and their own interest, and that the centralized approach, as dictated by our world’s central banks, will be come to be viewed as a false hero.

Last year, we referenced a growing illiquidity in the investment markets. Now, we see growing instability as central banks push liquidity into the system, perverting the normal setting of prices. Today’s economy is far from a normal or true market environment, and we continue to tread very carefully with about 40-50% of our portfolios sitting in cash and cash equivalents.