We would like to introduce Nobuya Nemoto, our guest for this month’s newsletter. Nobu has been a great resource to Auour for the past year as we all navigate a unique economic landscape.

“Inflation is the tiger whose tail central banks control,” according to the ex-Chief Economist of the Bank of England (forced to resign in 2021 from the Old Lady as his hawkish view clashed badly with the consensus within the MPC).

Using the same metaphor, one of the key tenets of modern monetary policy is the belief that the art of enchantment (“2% inflation target”) can be relied on to work its self-fulfilling magic in keeping the tiger asleep. “Magic” because to the Fed’s own admission, the theoretical and empirical foundation of how expected inflation influences realized inflation (including its causal relationship) is rather shaky, at least much less proven than the good old-fashioned employment-inflation trade-off.

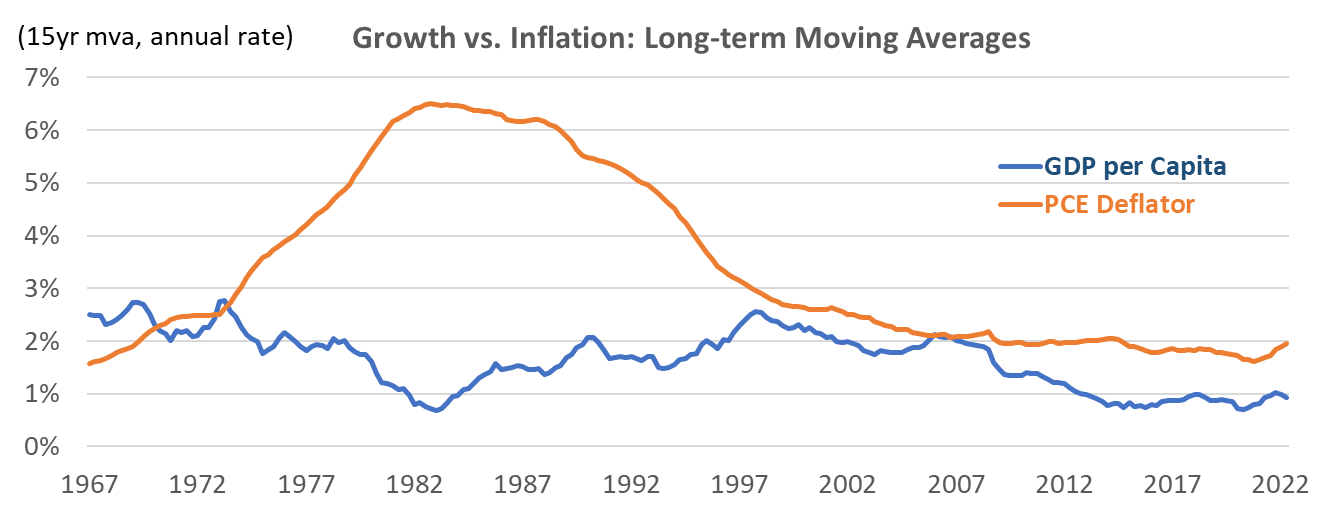

Inflation was indeed largely well-behaved over the past couple of decades (till 2021, that is). Central bankers across the G20 have taken credit as their own achievement, tacitly ignoring a happy confluence of other socio-economic undercurrents that could have been at play (globalization, the rise of Asian manufacturing supply powers, the spread of competition enhancing information technology, ex-communist countries joining the fray as significant commodity producers, relative fiscal conservatism, the demise of whatever was left of organized labor, etc.). [Auour Comment: We have been referring to this as the NICE period.]

Statistically, the problem could be restated as whether prices/inflation can be assumed to be a stationary process (i.e., stable sample mean, variance, etc.), like (real) GDP growth. If it is, any deviation from the mean (“2% inflation”) is always “transitory” by definition and will mean-revert sooner or later. A more extended history tells us that inflation has been anything but stationary.

It’s becoming increasingly clear that it will take time for the FOMC to readjust its lopsided response function defined by years of focus on “systemic risk” and “zero bound.” The Japanese “lost decades” was a distracting reminder of the clear and present danger. At the same time, Bernanke and Yellen made their academic careers studying the 1930s and the failure of the Fed to intervene back then.

In June, Chair Powell justified the Fed rate hike on risk management grounds. But seen globally, the risk that needs to be managed has come to encompass the institutional independence of central banks. Australia recently launched a review of the RBA after the institution was criticized for delaying interest rate rises even as inflation took hold, prompting its governor to describe its forecasting as “embarrassing.” In the UK, Liz Truss, the likely next PM, has also promised a review of the Bank of England and its independent decision-making on interest rates. The stakes are high and getting higher…

Nobu

P.S. Back in February 2021, Andy Haldane – then the Chief Economist at the Bank of England – warned against the upcoming spike in inflation in his last speech just before being booted out: “Inflation: A Tiger by the Tail?”:

“Inflation is the tiger whose tail central banks control. This tiger has been stirred by the extraordinary events and policy actions of the past 12 months.”

“…there is a tangible risk inflation proves more difficult to tame, requiring monetary policymakers to act more assertively than is currently priced into financial markets.”

“…the greater risk at present is central bank complacency allowing the inflationary (big) cat out of the bag.”

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/speech/2021/february/inflation-a-tiger-by-the-tail-speech-by-andy-haldane.pdf?la=en&hash=78C0DB3A631A7B9E2DF6EFBCFE9B3D138D87C449