Adjusting the Equation in Real Time

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M).

The above equation provides one way to conceptualize economic activity for a country. It makes the relationship between Consumption (C), Investment (I), Government spending (G), and the difference between exports and imports (X-M). Simple in form. Impossibly complex in function.

For decades, the U.S. economy advanced on a set of shared assumptions: cheap goods from abroad, stable institutions at home, and a government that could run persistent deficits without anyone raising too many concerns. Then came the new administration — and with it, a growing sense that none of those assumptions are sustainable anymore.

And as we have experienced over the past three months, they’re not thinking surgically — they’re going straight for the shock paddles. Each part of the economic system is being jolted: not because it’s entirely failed, but because they fear that without intervention, it soon might. Secretary of the Treasury Bessent recently called this moment one of “strategic uncertainty” — a phrase that captures the strange tension of bold action under fragile confidence.

What’s striking isn’t just the presence of significant change — it’s the simultaneity of it. Each element of the GDP equation is being pulled into the reform agenda.

A quick aside. We will spare you all any political opinions we may have, as they are meaningless when it comes to investing. Instead, we want to discuss the various puzzle pieces that we see in our attempt to see the larger picture. We should note that this discussion will not result in a change to our investment directions. Our investment process continues to be built on time-tested empirical studies that measure investor behavior and risk tolerance within the global investment ecosystem. Attempting to develop an economic forecast when there is so much uncertainty is unproductive and, in this case, manic.

Upon the changing landscape, two questions come to mind: 1) Why the urgency around government spending, and 2) Why the need to forcefully restructure trade? It appears that those two questions are at the root of many of the policies being enacted.

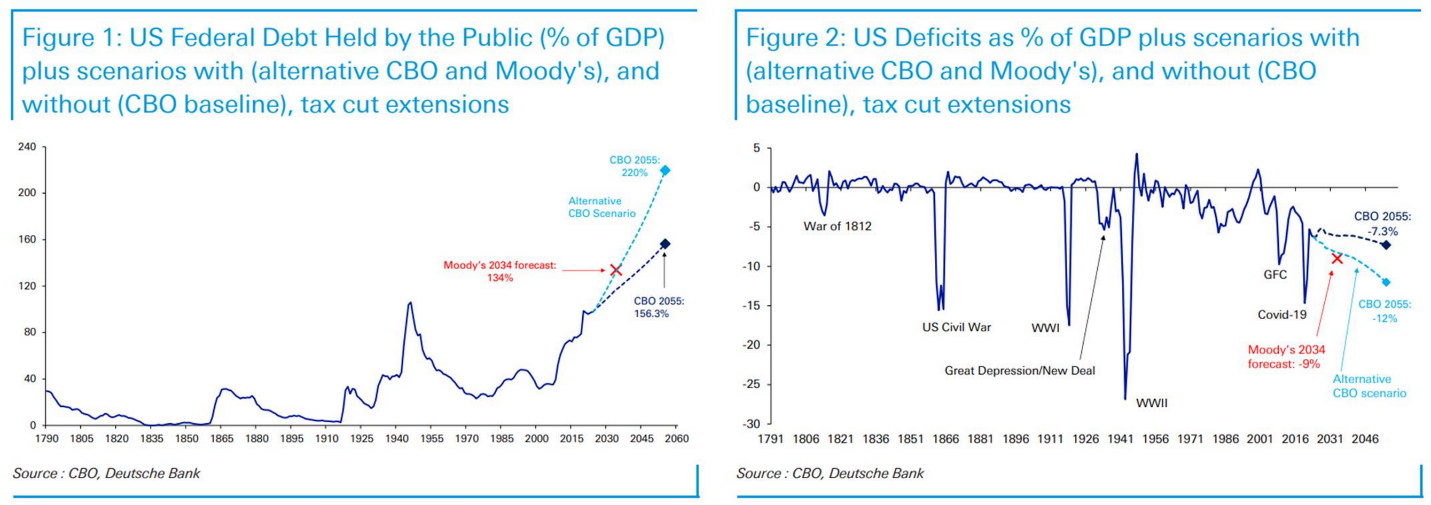

The answers to those questions may substantiate the need for such drastic adjustments. The answer to the first question revolves around a material change in deficit spending over the past decade. As the Deutsche Bank chart below shows, the U.S. has been running an extremely large deficit, even as the economy continues to chug along at a steady pace. The possibility is that the country may enter a precarious situation, which has led other countries to experience economic shocks as they approach a debt-to-GDP ratio of 150%. Is the U.S. comparable to those other countries that hit that turbulence? No, but do we  want to test it?

want to test it?

The answer to the second question appears to be the growing concern amongst both political parties that the U.S. needs to reduce its dependence on China. The new administration has added color to this discussion, believing that the era of the globe having a single global power is over, and we are back to a multipolar global environment. With the fall of the USSR, the world saw the U.S. fill the vacuum. Over the past two decades, China has grown to a size comparable to that of the U.S. in terms of economic strength and global reach. Right or wrong, the new administration sees a need to adjust decades-long policies to a new reality.

As stated earlier, the path being chosen touches and tests every component of the equation. Although the U.S. consumer is in strong shape, consumption is entering uncertain territory. For years, Americans have benefited from a global trade system that prioritized cost efficiency, even if it meant geopolitical dependency. It led to two decades of pricing disinflation. That changed somewhat under the prior administration as concerns about global warming led some to shift from the focus on faster, better, and cheaper to faster, better, cheaper, and less harmful. The new administration wants to refocus attention on faster, better, cheaper, and more strategic solutions. With the drive for new tariffs and supply chain reshuffling now on the table, it isn’t easy to imagine an environment where goods pricing does not need to adjust to a higher norm. That may serve strategic goals, but it also tests the limits of consumer tolerance in a system that has long relied on abundance at low cost.

Investment plans are also undergoing significant realignment. New policies and trade negotiations are driving new investments into the U.S. for sectors such as semiconductors, artificial intelligence infrastructure, and domestic energy production — areas viewed as essential not just for growth, but also for sovereignty. This is likely to have a positive impact, although there is uncertainty surrounding the timeframe. For example, we recently read “Apple in China” by Patrick McGee, which highlights the impact that corporate investment can have on a country. He highlights that Apple’s move to China for manufacturing at the turn of the century resulted in Apple training over 28 million Chinese in leading-edge manufacturing practices. Interestingly, he draws an analogy to the Marshall Plan following World War II, which helped rebuild Europe. Using that as a measuring stick, Apple’s investment in China was equivalent to the size of two Marshall Plans focused entirely on one country.

Government spending is undergoing philosophical triage. The deficit is growing, the national debt is flashing warning lights, and the last of the major credit agencies just downgraded U.S. sovereign debt from AAA. So, while the dollar remains dominant for now, there’s less breathing room than there used to be, especially if pundits are correct about the fear of China’s growing global footprint. Few will question the inefficiency in federal programs, but the current actions are likely to lead to the cutting of muscle, not just fat. With government spending accounting for around a third of the economy (larger for specific sectors), a significant adjustment in spending will likely have ripple effects for some time as public and private institutions adjust to a new environment.

And then there’s trade — the (X–M) term that used to live quietly at the end of the equation but is now center stage. Reshoring and “friend-shoring” have replaced globalization as policy priorities. The U.S.-China relationship has shifted from pragmatic interdependence to strategic decoupling. The “Red Curtain” that seems to be rising now is more complicated than the Iron Curtain ever was: it’s not just ideology, it’s supply chains, pricing power, capital flows, and trust.

As engineers, we understand that every equation comes with error bars for each component, which help to frame the potential variation in calculations. Those have grown over the year, suggesting that we are in a period of greater uncertainty. The economy isn’t falling apart, but it is being reassembled while it continues to operate. Markets, naturally, are struggling to translate intent into likely outcomes. Earnings forecasts for 2025 came down in the early part of the year but have remained surprisingly firm, high single digits for the S&P 500 — but there’s a growing sense that conviction in any direction could be dangerous. Forecasting in an environment where the inputs are still shifting is like trying to steer with a compass during a magnetic storm.

In moments like these, it’s easy to mistake uncertainty for collapse. But there’s another reading, too — one rooted in generational cycles. The Fourth Turning, by Strauss and Howe, describes a recurring pattern of societal reset, in which old institutions falter and new norms are forged under pressure. These periods are messy, but they are also necessary. Reform doesn’t happen in spring. It starts in winter, when the ground is frozen, and the future looks hard.

There’s no guarantee that the current policy direction will succeed. Still, the underlying goals — rebuilding institutional credibility, reshaping critical dependencies, and revitalizing productive capacity — respond to concerns that are broadly acknowledged, even if the strategies provoke debate. This isn’t about choosing optimism or pessimism. It’s about humility. About recognizing that we are mid-transition, and that clarity, like a harvest, doesn’t arrive the moment seeds are planted.

So we stay alert. Strategic uncertainty doesn’t call for bold predictions; it demands humility and vigilance. We ground our approach in signals that have proven their worth through past periods of economic and political unrest, resisting the urge to chase headlines or cling to tidy narratives. We remain skeptical of certainty, and cautious of promises—whether they suggest smooth sailing or inevitable collapse. Because in times like these, it’s not the volatility that breaks portfolios. It’s overconfidence in a single path forward.