The Oracle of Omaha, Warren Buffett, is a consistent optimist about the power of investing in the U.S. equity market. Though known as a selective investor, he advocates that the average investor buy and hold a slice of the entire equity market. As a fundamental principle, we agree. But for those of us who aren’t in his unique position as one of the richest people on the planet, sometimes we need access to that slice.

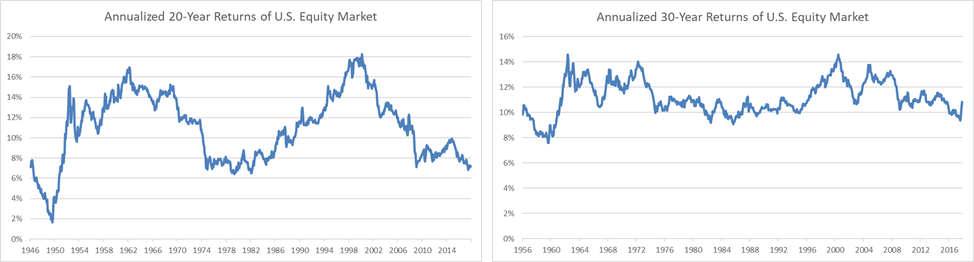

As the graphs below show, Buffett is right over the long-term. There are few periods when equities did not produce superior returns on an annualized basis over 20- and 30-year holding periods. It might catch your eye in the 20-year graph that buying into the market even at the worst time still produced a 2% annualized return. In the 30-year graph, buying at the worst time still produced an annualized 8% return. Not bad for exceedingly mis-timed investments!

Although it’s a true story that such returns are available for people who can stick to the investment through thick and thin, there’s a twist: If you need funds concurrently with a major drop in the market, you will be locking in sub-optimal returns by selling at the worst time and missing out (at least partially) on the rebound.

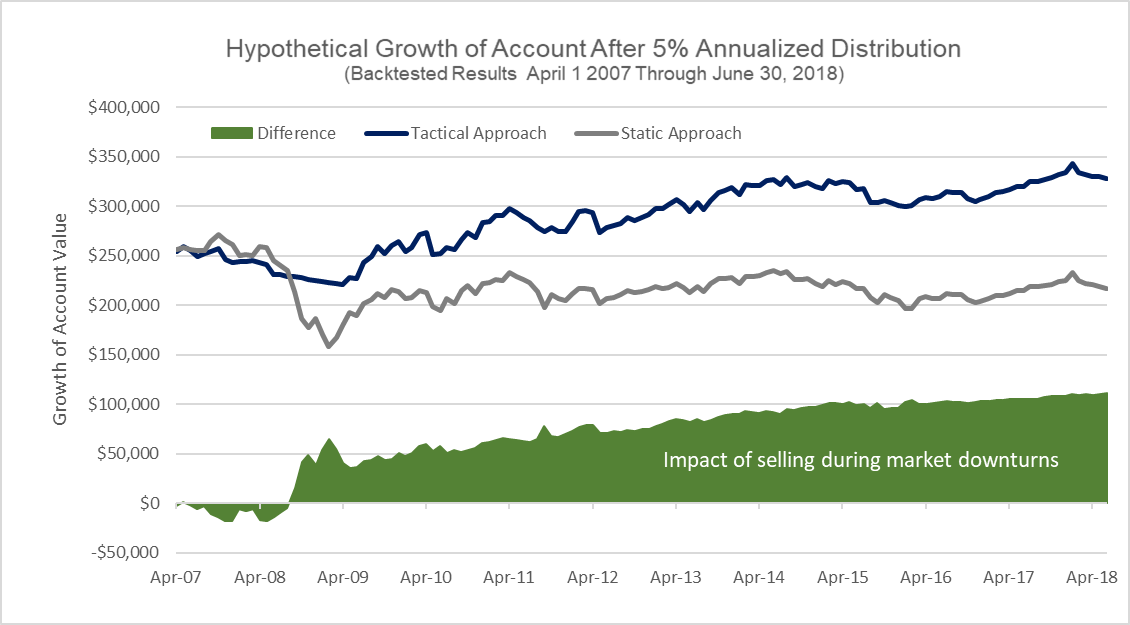

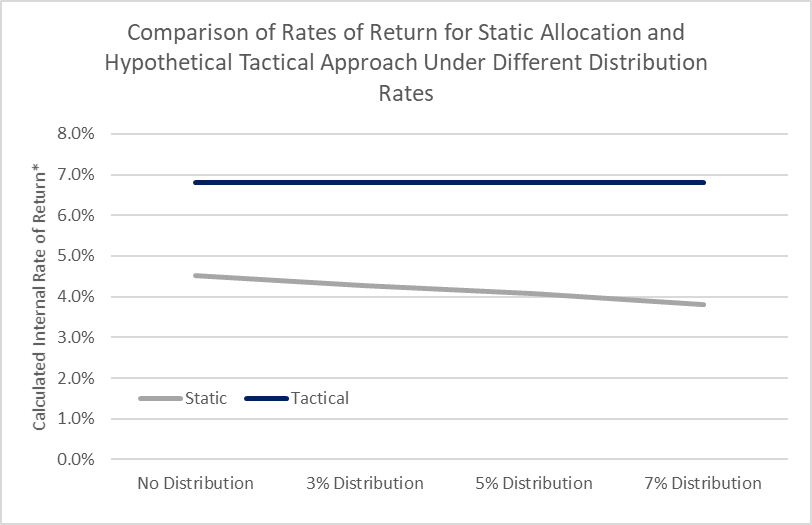

We analyzed the impact of distributions at various levels on a set amount of money invested in the market broadly as it runs through an economic cycle. In this analysis, the investor receives regular monthly distributions equal to (annualized) 3%, 5%, and 7% of initial funds. For comparison’s sake, we compared those to a scenario where no distributions are made. In these scenarios, we used the most recent economic cycle, investing into a static 60/40 global portfolio near the peak of the market in 2007 as it will show the impact of a major market correction.

The difference between the outcomes is startling. Buying into the investment cycle near the top of the market had a material impact on the internal rate of return, but the subsequent market rebound made the returns tolerable. However, when the investor received systematic distributions throughout the investment cycle, the returns were reduced such that the investor actually lost principal, even before considering the impact of inflation!

We highlight the impact of systematic distributions to show the risks of static asset allocations and the “weather the storm” mentality it requires. On the other side of the spectrum sits tactical management which comes in many flavors. For Auour, we are particularly interested in an approach that navigates away from major market downturns by moving to cash in times of anticipated market duress. We believe the ability to mitigate large losses from the market’s normal, yet painful, volatility can have a significant impact on portfolio returns and a client’s success of reaching their retirement goals.

The chart above shows the impact, assuming success, of positioning a portfolio for those rare, yet material, downturns by tactically protecting savings using cash. Under a regular, static distribution scenario, you sell securities no matter the market price, which is detrimental when markets turn materially lower.

The chart above shows the impact, assuming success, of positioning a portfolio for those rare, yet material, downturns by tactically protecting savings using cash. Under a regular, static distribution scenario, you sell securities no matter the market price, which is detrimental when markets turn materially lower.

However, if you mitigate the downturns by moving some funds into cash, the regular distributions can come from the temporary cash position and not from securities that are, for the time being, losing value. As a result of this form of tactical management, you have a better chance of seeing increased returns and achieving more of the market’s potential.

Obviously, no solution is perfect. Some tactical approaches come with more risk and likely higher turnover. However, that does not need to be the case as practiced by Auour. The analysis shows that the world investment markets produce positive outcomes the majority of the time. Historically, it has been seldom that markets experience deep and enduring downturns, lending support to Mr. Buffett’s advice. However, no matter how infrequent, the resulting damage by a downturn to a retiree’s portfolio can be significant and argues for a tactical approach to protection for us non-billionaires.

* We utilize Internal Rate of Return (IRR) for this analysis as Time Weighted Return calculations do not take into account the sequence of returns and the cash flows’ impact on a client’s outcome.

Caveats

This analysis relies on the hypothetical backtests of the Auour Regime Model and the asset allocations that it would have signaled as if the firm and the model were in place over the market cycle analyzed. Auour started managing outside assets in the Fall of 2013. Hypothetical results are net of estimated transaction costs and management fees.

There can be no assurances that the firm would have implemented the model as it was tested or that the resulting performance would have been obtained. As with any hypothetical analysis, it is error prone and suffers from at least hindsight bias. Though attempts were made to minimize biases and errors, no one should rely solely on the results presented as factors and conditions can not be precisely replicated. And, what should be obvious, past performance, be it real or hypothetical, can not and should not be relied on for indications of future returns. Though our mothers may state otherwise, none of us are perfect.