Increasing Fragility

“Some things benefit from shocks; they thrive and grow when exposed to volatility, randomness, disorder, and stressors and love adventure, risk, and uncertainty.” -Nissim Nicholas Taleb

Well-intentioned plans can bring unintended consequences. The world’s major central banks have been adding stimulus to the global financial system, hoping to lessen economic volatility and minimize the chance of a material slowdown. However, the result of their actions might be to increase the fragility of the institutions they intend to strengthen.

We have written about the unnatural negative interest rates in many developed nations outside the U.S. (See, “The Sound of Money Dying”) We have highlighted the political uprisings gathering steam around the globe that authoritarian-leaning governments are attempting to suppress. We have described the issues tied to liquidity—or lack thereof—in Europe and Asia, and our own central bank’s attempt to mask a liquidity problem in the U.S. with an explosive infusion of dollars into the financial system. These global events are not independent of each other. They may represent the late stages to the economic party when the party-goers attempt to keep the party going by breaking out more libations.

The central banks are acting to lessen the pain citizens feel from normal economic fluctuations. But we believe that just as total energy is conserved within a physical system—being neither created nor destroyed—volatility is conserved in an economic system. It’s there. And attempting to suppress it in one place intensifies it in another, or results in a larger dislocation later. We experienced this before, when the Federal Reserve pumped money into the system in front of Y2K leading to an asset bubble in technology companies. Again, when they kept rates low into the Great Financial Crisis leading to overindebted consumers. We fear we are setting up for another rough ending to the party soon.

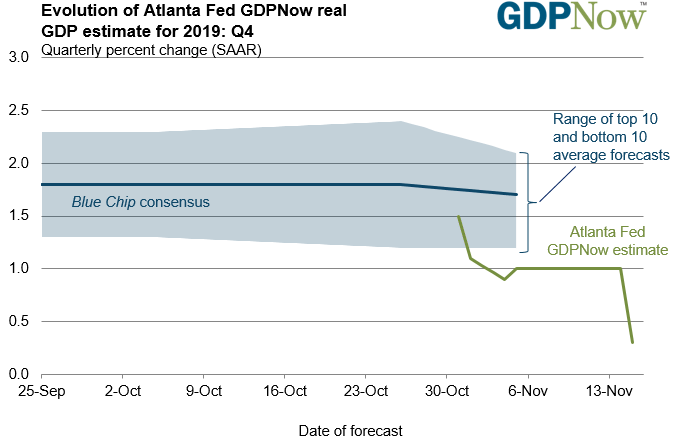

The U.S. stock market is hitting new highs even as we simultaneously see widening fractures in the system, such as the recent significant slowdown in current GDP.

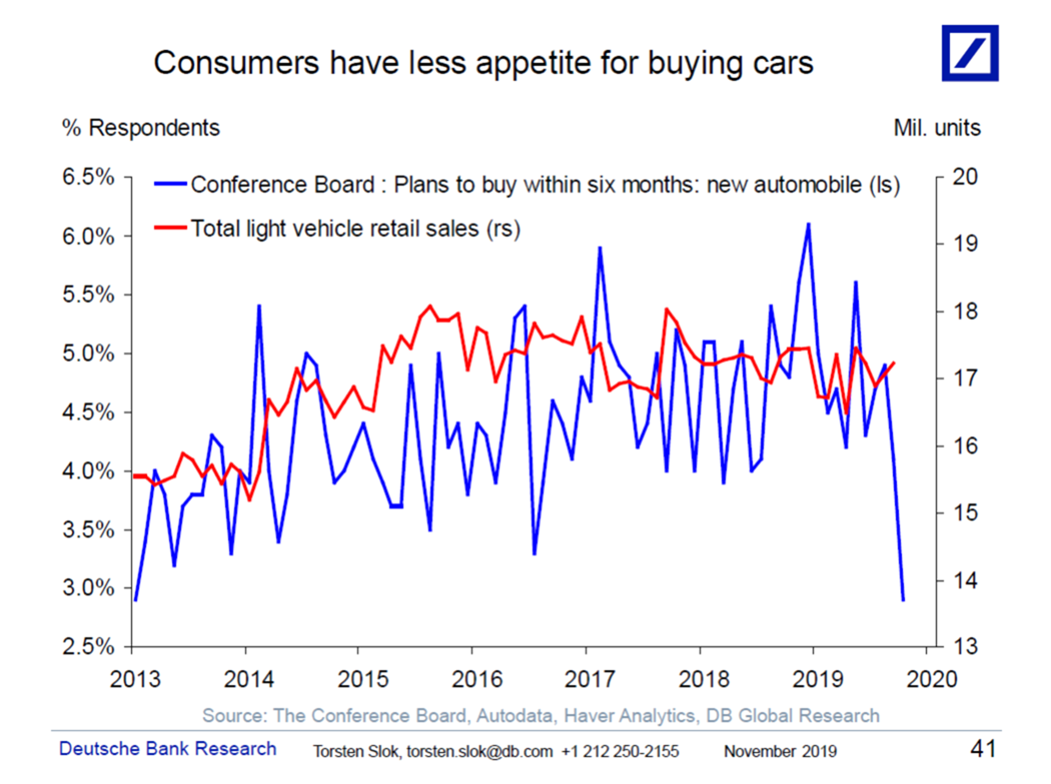

U.S. consumers, the only cylinder still firing in the global engine, are showing some early signs of strain. Various measures of consumers’ intent to make major purchases are softening.

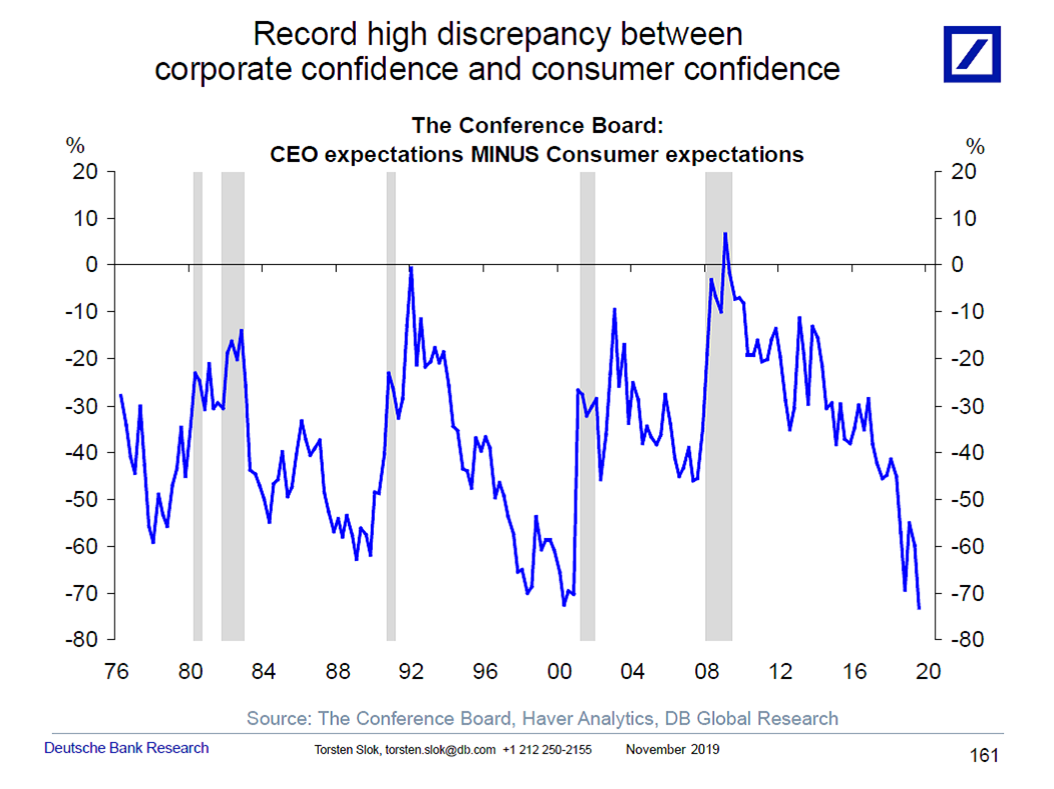

And their employers are also expressing significant concern. Historically, when there is a disconnect between employer and consumer expectations, unemployment rises. We are now at the largest gap in expectations since the Technology Bubble.

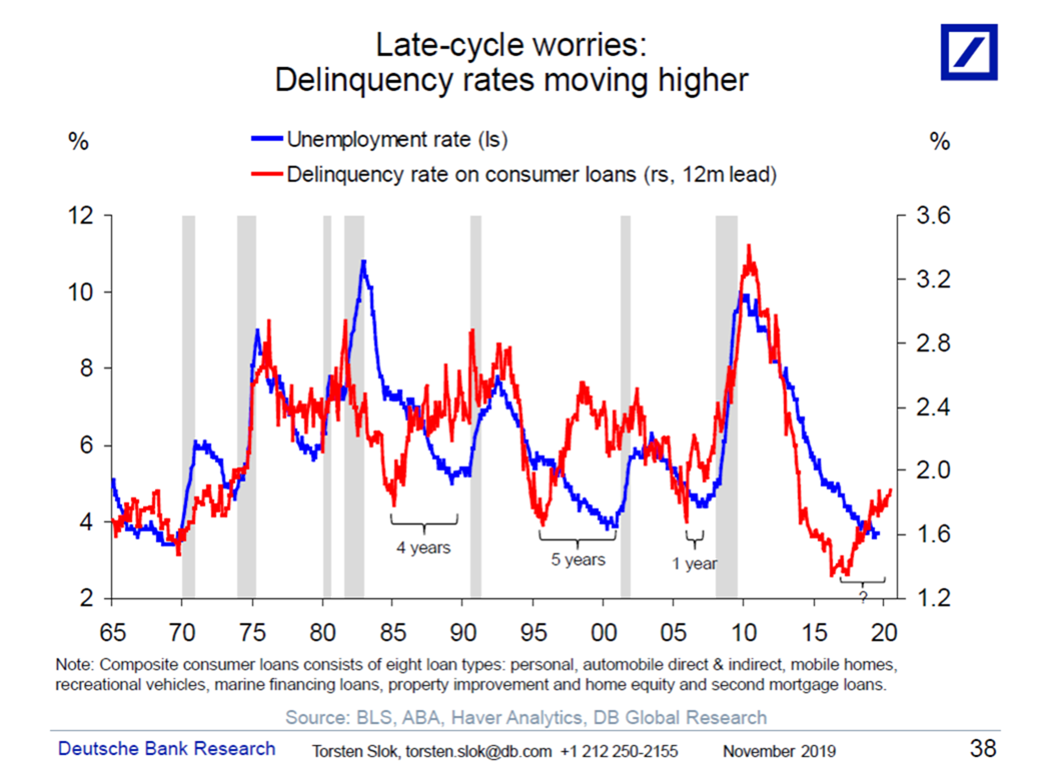

One indicator of strain on the U.S. consumer is indicated by the increase in delinquent debt. Consumers have been spending at a rate above their ability. In other words, acting as though the party will never end.

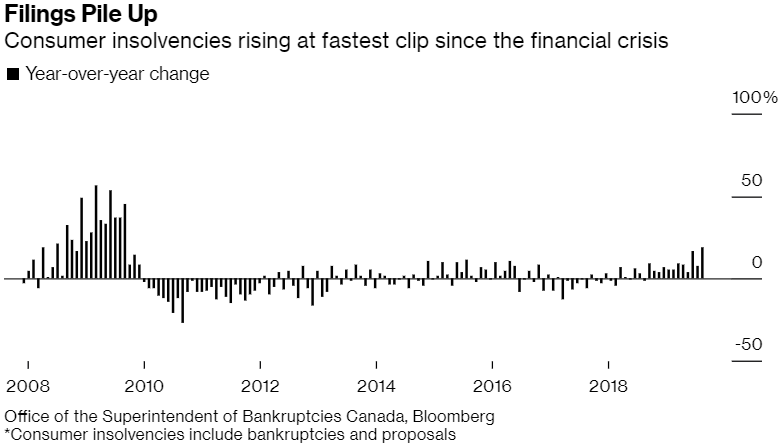

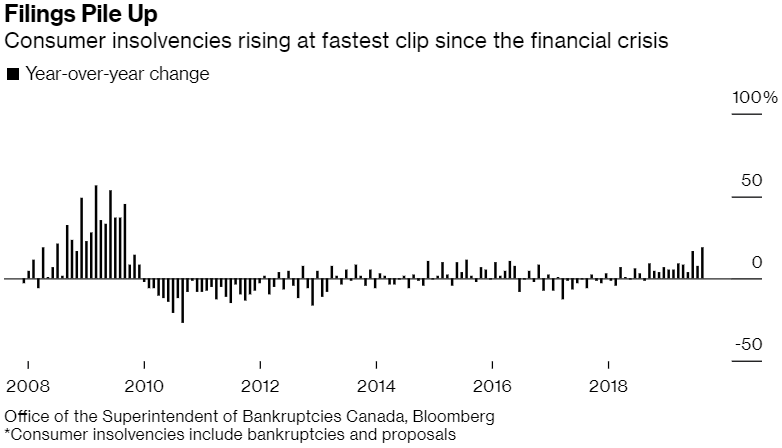

Our neighbor to the north is also seeing strains in its consumer segment, with bankruptcies on the rise in Canada at the fastest rate since the Great Financial Crisis.

Our risk detection model at Auour does not directly take into account consumer enthusiasm and debt, as shown in the figure above, but those data help explain why our readings now encourage being conservative. The signals we use to measure market risk blend past growth with forward-looking datapoints. Recent growth continues to be positive, but, as we have mentioned in other discussions, looking only at those is like driving a car by looking at the rearview mirror. (You’ll be fine on the straightaways but won’t fare so well on the turns!)

To understand the upcoming turns, then, we need to assess signals that can be predictive. A number of those signals, in our opinion, are liquidity-based. In other words, they help us dissect when complacency in certain investment markets has built to the point that getting out could cause significant economic disruption. Picture this: it’s hard to push a hundred people through the exit door when the theater is on fire.

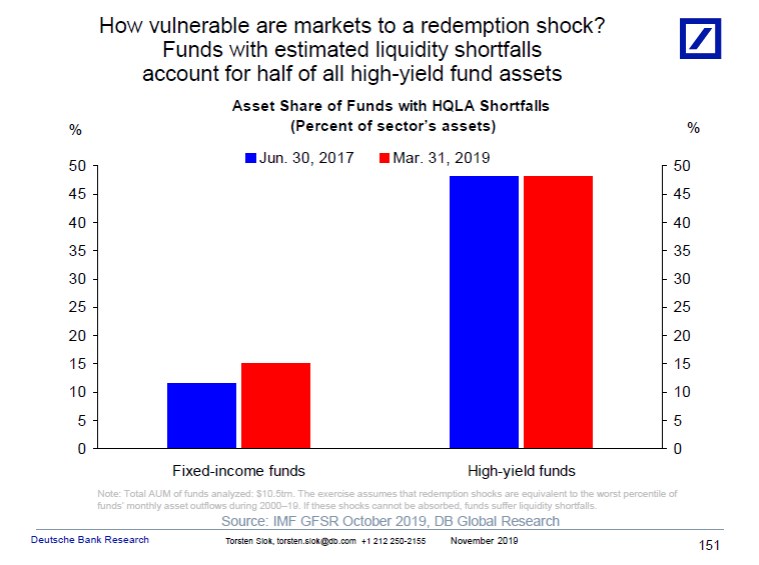

We have mentioned in the past that several European mutual funds have had trouble meeting redemption requests. Ultralow rates around the globe have caused many funds to reach for yield in unnatural ways. It may be fine if new dollars continue to flow into the investment but, much like musical chairs, you don’t want to be exposed when the music stops. We have increasing concerns that the music is in the last verse.

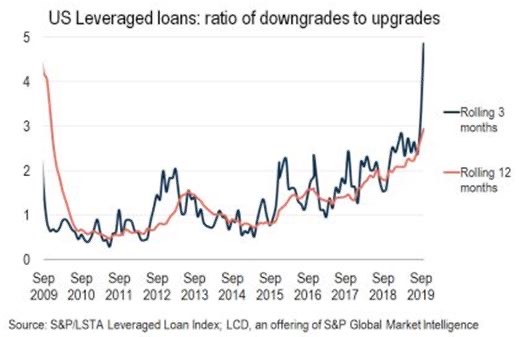

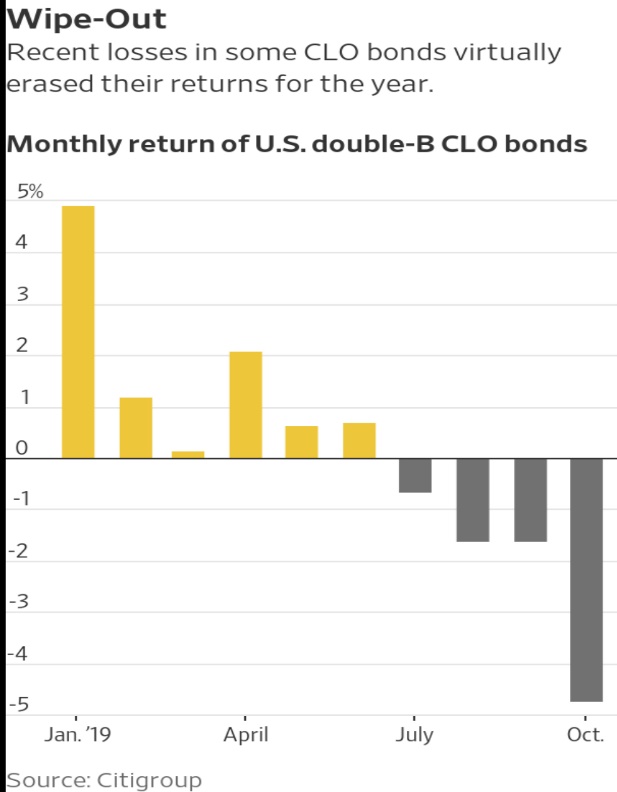

The lowest rated corporate bond market is showing signs of weakness now, as is the bank loan market—a market that has been a stable provider of returns since the Financial Crisis. And market participants are becoming more discerning. Although the economy remains strong to date, credit ratings within the loan market have recently deteriorated quite materially.

This phenomenon has resulted in significant losses and outflows from funds in the bank loan space. Part of that material decline, in our opinion, is the natural illiquidity of that asset class. Liquidity is there when there are buyers, but it quickly evaporates when investors turn into sellers.

We have become increasingly concerned also as we see a large part of the more popular high yield credit market carry ratings of high illiquidity. If those buyers turn into sellers, we fear that Europe’s redemption issues could spread to the U.S.

So, let’s sum this up…

Parties are fun. Hangovers aren’t. Central banks are acting as bartenders that are looking to make an epic party. Great intentions but the guests will suffer the consequences. The economy is showing signs of strain in liquidity and in pricing of some traditionally “safer” asset classes. As with any party, it does come to an end no matter how much the hosts want them to stay. Our signals continue to have us positioned defensively. Carrying on the party analogy, we have gotten our coats.