“The investor of today does not profit from yesterday’s growth.”

—Warren Buffett

The Quarter in Review

Compared with previous quarters, the third quarter exhibited considerably more volatility with little appreciation. Most investment markets are showing signs of exhaustion due to continued uncertainty about trade wars, the negative interest rates in most developed countries, and deteriorating economic readings. Over this past quarter, we have seen companies reduce their outlook for growth and earnings, for obvious reasons.

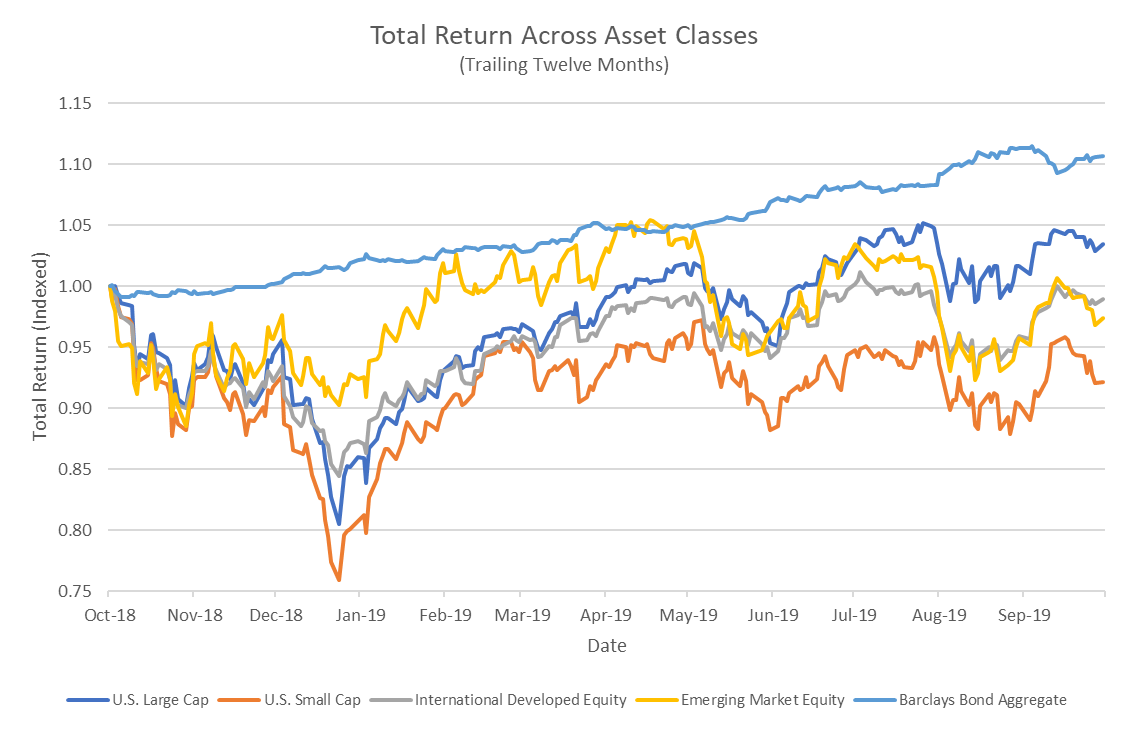

The U.S. continues to be the only large house in the neighborhood not on fire. Both developed international and emerging markets have deteriorated since the end of the second quarter. Economies outside the U.S. are very close to contracting, with no green shoots showing. And this weakness in the international markets has company. Smaller domestic firms have been experiencing losses, lagging their larger cousins in performance by almost 13% over the past 12 months. This is typical in a late-cycle investment regime, when investors abandon perceived riskier asset classes and hide in large, U.S. companies.

The preference of investors for fixed income asset classes continued this quarter as they outperformed most equity segments. Looking back over the past 12 months, this outperformance is nothing less than stunning, with 10-year Treasury notes producing a total return that is three times greater than the average performance of large U.S. companies. The interest rates are still dropping for the highest quality debt, but we are starting to see relative underperformance of riskier debt, another sign that we are in the later phases of this bull market.

The preference of investors for fixed income asset classes continued this quarter as they outperformed most equity segments. Looking back over the past 12 months, this outperformance is nothing less than stunning, with 10-year Treasury notes producing a total return that is three times greater than the average performance of large U.S. companies. The interest rates are still dropping for the highest quality debt, but we are starting to see relative underperformance of riskier debt, another sign that we are in the later phases of this bull market.

FOMO versus FOAL

Investors are experiencing an intense tug-of-war between two contradictory impulses: the fear-of-missing-out (FOMO) and the fear-of-absolute-loss (FOAL). Although these fears are often at play simultaneously, they are often felt more acutely at the beginning and end of the investment cycle. And the tugs back and forth are becoming more violent. We believe we are at the point now where a winner will likely show itself soon. Our signals continue to deteriorate, suggesting a higher probability of FOAL versus FOMO.

Investors are experiencing an intense tug-of-war between two contradictory impulses: the fear-of-missing-out (FOMO) and the fear-of-absolute-loss (FOAL). Although these fears are often at play simultaneously, they are often felt more acutely at the beginning and end of the investment cycle. And the tugs back and forth are becoming more violent. We believe we are at the point now where a winner will likely show itself soon. Our signals continue to deteriorate, suggesting a higher probability of FOAL versus FOMO.

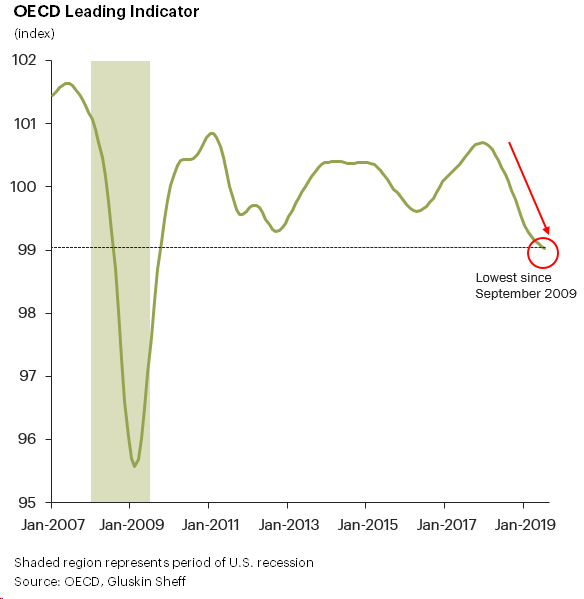

Growth is souring in many parts of the world and, as we have mentioned in our past commentary, is likely to impact the U.S. eventually—or more probably, soon. The leading international economic indicators for recession have hit levels not experienced since the Great Financial Crisis. This does not mean we have entered a recession, but it does suggest that confidence in future growth is dropping.

Although the U.S. has not registered recession-level readings yet, some of the countries we tend to think of major economic engines to the world are close. Germany, the largest European economy, is very likely in a recession. Factory orders, to emphasize just one metric, have declined on an annual basis for 15 months in a row. And the latest signals suggest Germany hasn’t seen the bottom yet.

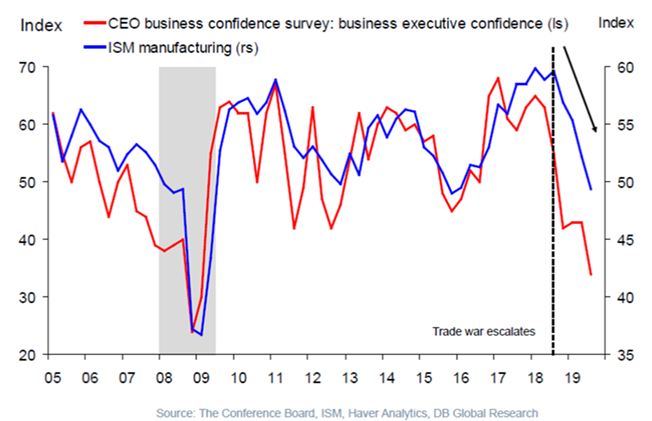

In corporate board rooms,  the global economic sluggishness appears to be causing concern. The business activities of CEOs point to diminished confidence. The CEOs influence economic activity, of course, via investing and hiring. It is unclear in the U.S. if they are simply reacting to economic news or acting to address specific issues seen within their own businesses. The increasing pessimism we see about the economy is following the reduction we are witnessing in manufacturing data.

the global economic sluggishness appears to be causing concern. The business activities of CEOs point to diminished confidence. The CEOs influence economic activity, of course, via investing and hiring. It is unclear in the U.S. if they are simply reacting to economic news or acting to address specific issues seen within their own businesses. The increasing pessimism we see about the economy is following the reduction we are witnessing in manufacturing data.

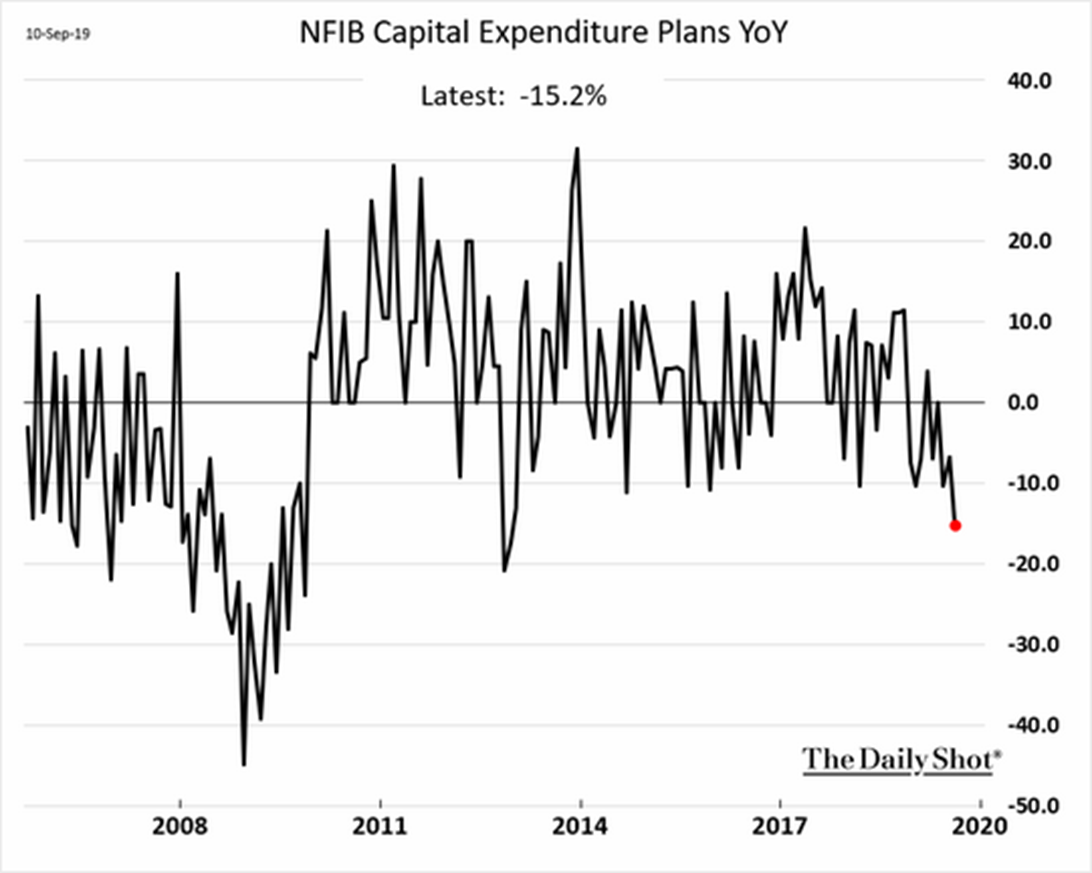

The tug-of-war between FOMO and FOAL is intensified by the mix of backward-looking data (i.e., past growth) and forward-looking data (i.e., future growth). Though current economic activity in the U.S. has been strong, future intentions are most definitely dropping. Optimists will defend their opinions by referencing recent growth. Pessimists will defend theirs by looking at the reduced future expectations for investment. We consider ourselves optimists at heart but looking behind us cannot help measure the severity of storms over the horizon. Plus, facing backwards makes us seasick, especially as the waters become increasingly rough.

The tug-of-war between FOMO and FOAL is intensified by the mix of backward-looking data (i.e., past growth) and forward-looking data (i.e., future growth). Though current economic activity in the U.S. has been strong, future intentions are most definitely dropping. Optimists will defend their opinions by referencing recent growth. Pessimists will defend theirs by looking at the reduced future expectations for investment. We consider ourselves optimists at heart but looking behind us cannot help measure the severity of storms over the horizon. Plus, facing backwards makes us seasick, especially as the waters become increasingly rough.

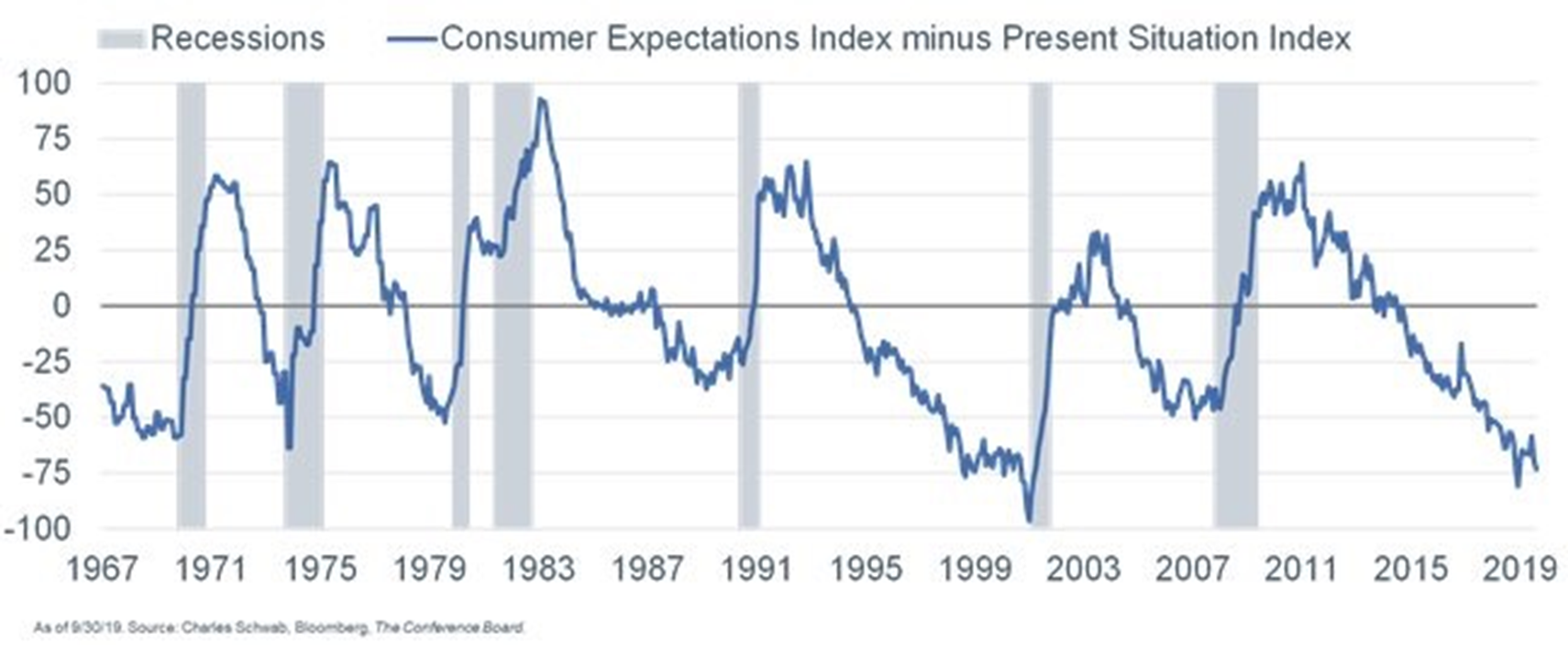

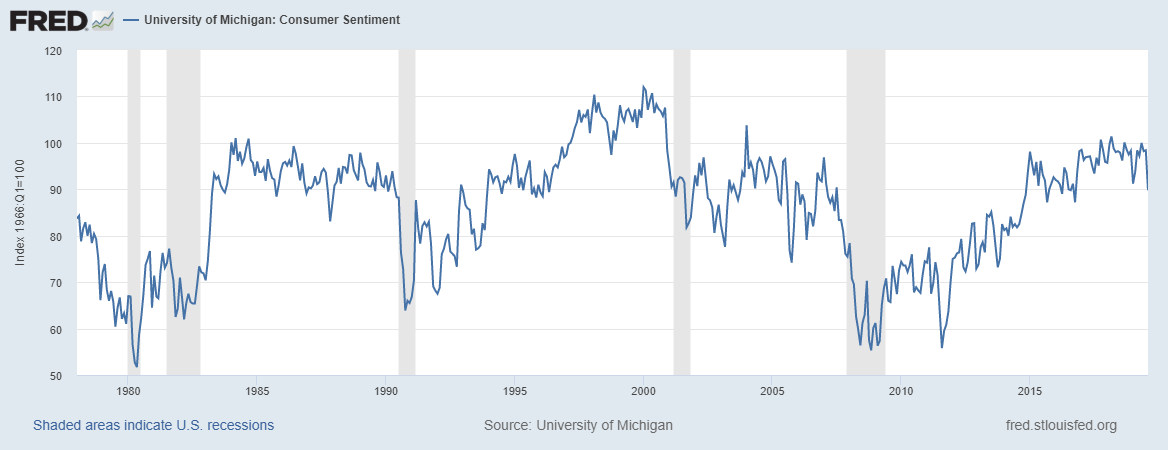

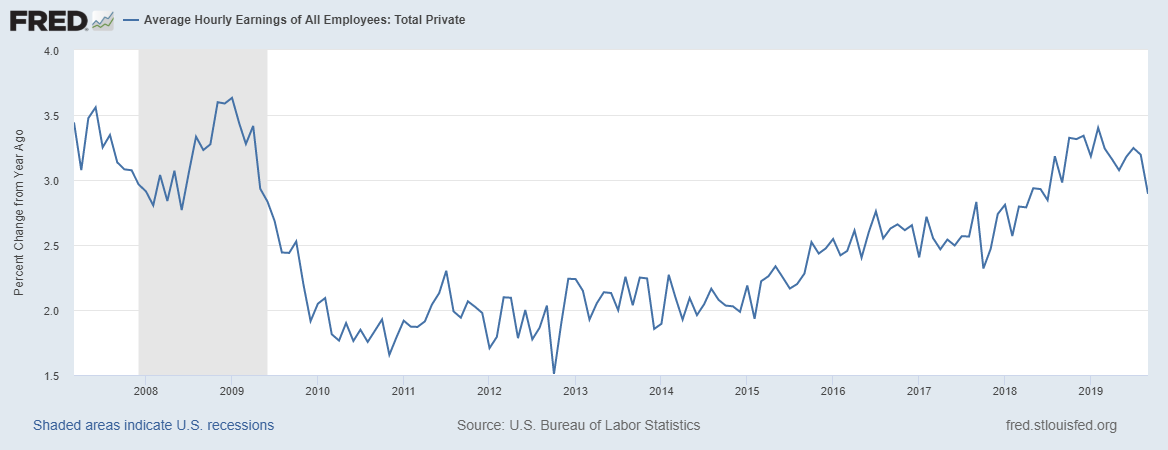

The world economy would be in much tougher shape if the U.S. consumer was cutting back. Consumers in the U.S. generate about 80% of all economic activity for the country. And with the U.S. having such a large appetite for imported goods, they can also sustain the economies of nations far and wide. However, we are seeing cracks in the apparently robust spending picture. Consumer data shows people are happy with the current situation, but less so than in the recent past. Add to this that they have a negative view of future conditions, and we certainly aren’t feeling bullish about a continuation of these spending habits, especially since we are now also seeing a deceleration in hourly earnings. These signals suggest to us additional slowing that has not yet worked

The world economy would be in much tougher shape if the U.S. consumer was cutting back. Consumers in the U.S. generate about 80% of all economic activity for the country. And with the U.S. having such a large appetite for imported goods, they can also sustain the economies of nations far and wide. However, we are seeing cracks in the apparently robust spending picture. Consumer data shows people are happy with the current situation, but less so than in the recent past. Add to this that they have a negative view of future conditions, and we certainly aren’t feeling bullish about a continuation of these spending habits, especially since we are now also seeing a deceleration in hourly earnings. These signals suggest to us additional slowing that has not yet worked  its way through the system.

its way through the system.

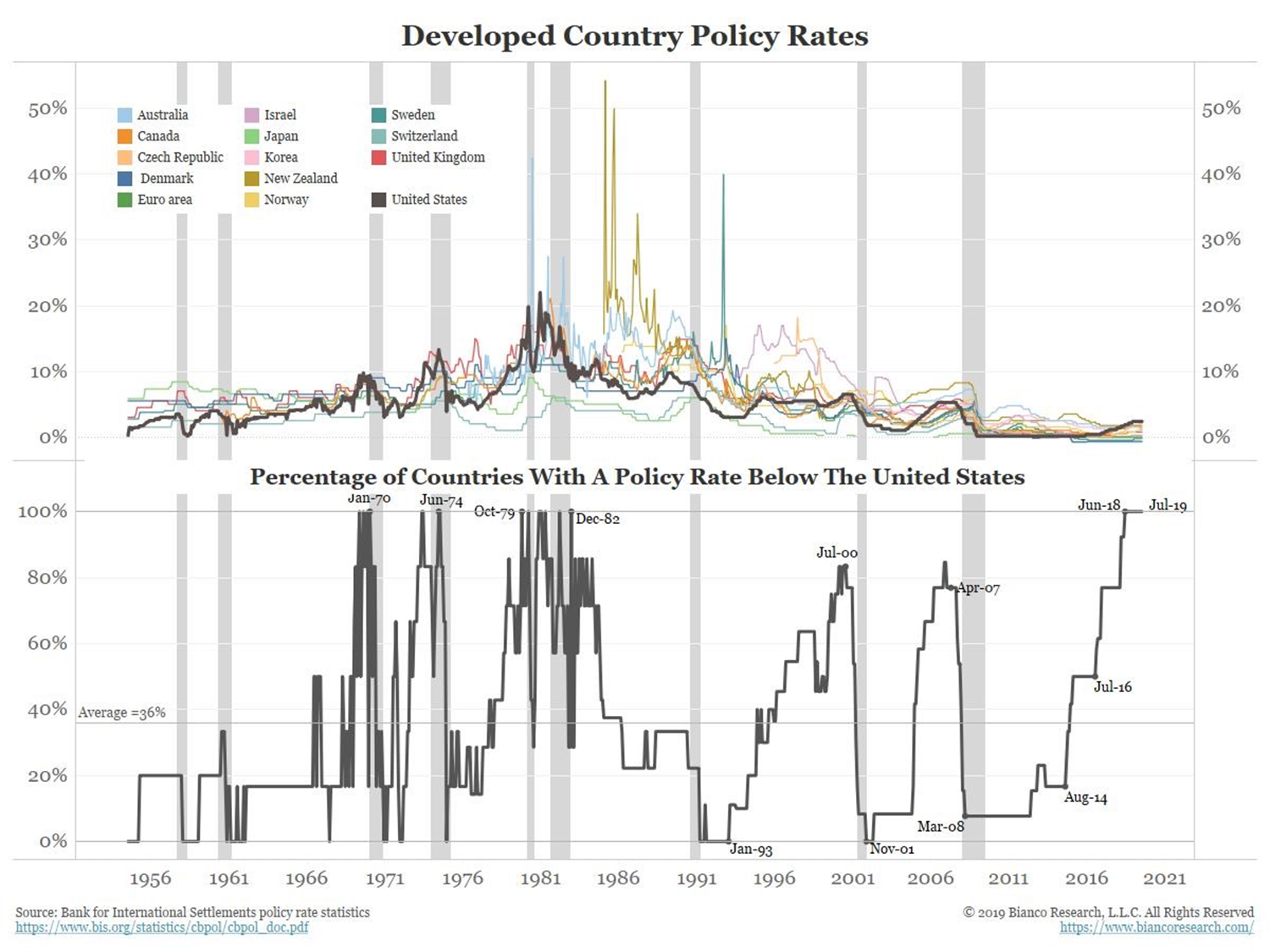

With increasing concern over the consumer, it is not comforting to see our credit models send warning signals. Though not a direct indicator, we think it’s interesting to look at the interest rates set by global central banks versus how they compare to the U.S. Federal Reserve’s rates. The U.S., for very good reason, is viewed as the most risk-free asset for most investors, no matter where they reside, so we would generally expect the rates to be lower than in riskier countries. It is therefore interesting to see many developed countries showing lower interest rates than the U.S. In the past, this has been a characteristic, perhaps more correlative than causative, reached just before past recessions.

With increasing concern over the consumer, it is not comforting to see our credit models send warning signals. Though not a direct indicator, we think it’s interesting to look at the interest rates set by global central banks versus how they compare to the U.S. Federal Reserve’s rates. The U.S., for very good reason, is viewed as the most risk-free asset for most investors, no matter where they reside, so we would generally expect the rates to be lower than in riskier countries. It is therefore interesting to see many developed countries showing lower interest rates than the U.S. In the past, this has been a characteristic, perhaps more correlative than causative, reached just before past recessions.

The juxtaposition of so many visible cracks in the global economic system with investment markets being near their all-time highs is dizzying. With the markets moving based on tweets and on see-sawing predictions about the state of the trade wars, the fact that slowing may have more to do with tired consumers than anything else has not been contemplated. We see such exhaustion as the bigger risk at this point. Investment markets are looking at the recent past, and, if the trade disputes are resolved, will be pricing as if in clear skies, neglecting the fact that it just might not be trade issues and tariffs slowing the global economy.

Conclusion

The conclusion from our last quarterly commentary still fits today:

“We have mentioned in prior communications that a mixture of greed and complacency can produce a dangerous concoction. We fear that many market participants today are acting on the expectation of positive outcomes at a time of increasing fragility.”

Towards the end of this quarter, our models pushed even further into a more defensive position. We currently hold between 40% to 50% of all strategies in very low-duration U.S. Treasury bills because we do not know any other means of protecting principal and maintaining liquidity. The fissures we have been monitoring are widening. They do not necessarily suggest the world is ending, but higher levels of fragility argue for more support within a portfolio. For us, that means value-protecting assets, such as short-duration U.S. debt instruments, that permit enhanced liquidity.