In our May 2021 newsletter, Breaking Windows, we discussed inflation and its impact on the investment markets. We said the primary drivers of inflation were the large stimuli injected unevenly into the global economic system through governments and central banks. That newsletter focused on one side of the equation—demand—and in it we noted: “There is an argument to be made that persistent inflation is unlikely without a scarcity of core, non-discretionary inputs. (Think back to oil in the 1970’s).”

In May, we hoped inflation in the U.S. would be transitory as the world reopened with pent up demand. However, what we fear now is that pockets of scarce supply will continue to put upward pressure on prices because ongoing pandemic-induced precautions and changing priorities by governments around the globe appear to be entrenched.

Over the previous four decades, the world’s population has experienced a fantastic non-inflationary, consistently expansionary (NICE) economic landscape. The term NICE was coined (pun intended) by the former head of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, who said, in 2008, that the U.K. was likely exiting this golden period. He was speaking only of the U.K., but he could have applied his assertion to most developed countries. Up until the Global Financial Crisis, the U.K. and the world at large had been experiencing moderate global inflation and relatively smooth economic expansion. Since his comments, and until the present moment, inflation has continued to be moderate, but economic growth has become more volatile as economies increasingly depended on easy monetary policies and financial leverage. Today, with inflation perking up and unstable economic growth, Mr. King’s end-of-NICE concerns might finally be coming to fruition.

The global NICE period started in the mid to late 1970s as the U.S. started a wave of privatization, deregulation, and the breakup of government-enforced monopolies (e.g., Ma Bell), all of which reduced barriers to entry, expanded the competitive landscape, and drove a multi-decade investment cycle focused on creating better, cheaper, and faster solutions.[1] It was not only the U.S. that saw this low inflation period of growth. We saw it, too, with the fall of the Berlin Wall, and with the integration of the Iron Curtain countries into the Western European economy as both end markets and centers of manufacturing. The period got new momentum as communist China opened a bit, offering a large untapped labor force and, over more recent decades, a prosperous consumer hungry for Western goods.

Once static industries were able to opportunistically adopt technological innovations and cross borders to source optimal labor and service new end markets, economies of scale brought more value to an expanding addressable market. Over the course of three decades, the world witnessed a dramatic decrease in extreme poverty. More than a billion people moved up the wealth curve, producing new consumers along the way. The immense new resources allowed for a non-inflationary environment to flourish even as economies across the globe grew rapidly.

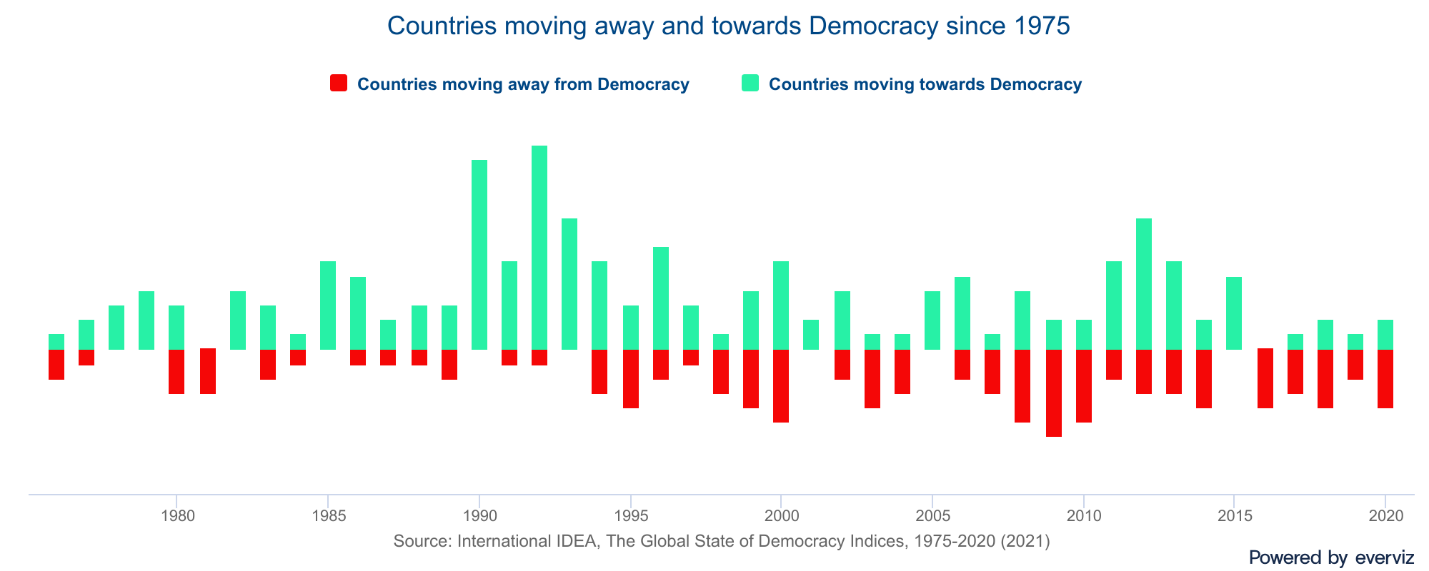

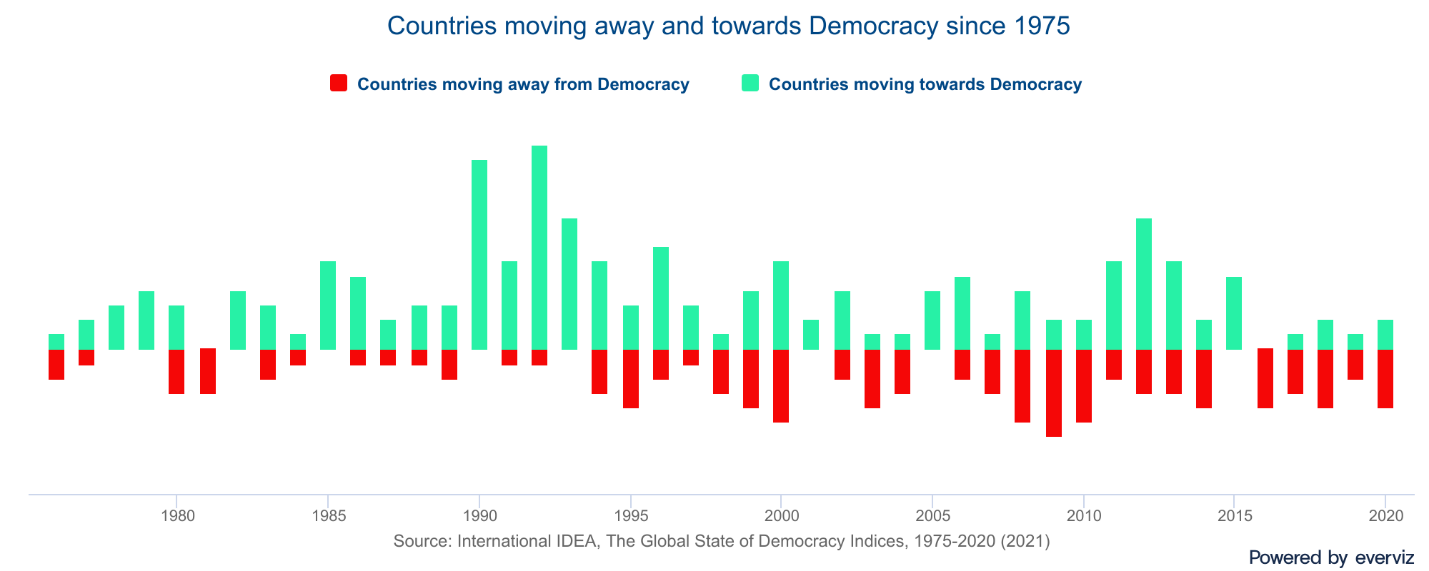

The IDEA report also highlights that the pandemic has led to a surge in authoritarian behavior by even the most democratic governments, as many around the globe experience mandatory lockdowns and travel restrictions. Pandemic-induced scarcity through restricted movement has caught many’s attention, but other factors not necessarily related to Covid have led to a material change in the availability to economic inputs.

Let’s use three examples—the global energy sector, U.S. supply chains, and the global labor market—to explore this cause and effect.

Regarding energy costs, governments around the world have been pushing for greater reliance on renewable energy. Developed market countries have quickened the prioritization of renewable energy as they feared the impact of their use on the environment. The U.K. moved aggressively into wind power, simultaneously reducing their investments in fossil fuel facilities, which resulted in energy shortages recently when the wind wasn’t blowing. Europe has been aggressive in moving away from traditional energy sources, as well. France—which has the second largest reserve of shale gas in Europe—banned fracking in 2011, and in 2017, it banned all new oil development, setting the stage to cease all production by 2040. Germany enacted legislation in 2011 to move away from nuclear energy, causing a heavier intermediate-term reliance on fossil fuels at the same time the government was also restricting investments in that space.

Restricting production does not correspondingly change demand, however, which has continued to grow in these countries. As a result, France and Germany have become increasingly dependent on Russian natural gas at a time when Russia is flexing its muscles politically and economically in direct opposition to European democratic ideals.

Our second example is the U.S. supply chain.

Monetary and fiscal stimuli allowed for greater consumer demand during the pandemic than expected, forcing companies to play catchup after depleting inventories at the start of the pandemic. Many firms are also changing their supply strategies from a pre-pandemic, just-in-time approach to a post-pandemic, just-in-case one. Even so, misjudging demand does not explain why port congestion— understood to be a major contributing factor to the U.S. supply chain problem—is worse on the West Coast than the East Coast. The East Coast (representing about 19% of U.S. import capacity) is not experiencing the same level of congestion as ports in California (that represent about 28% of import capacity). If we look under the hood, the problem may exacerbate the downstream effects of California’s regulation of ride-sharing companies.

The American Trucking Association estimates that the U.S. is short about 80,000 truck drivers. Yet, reports estimate that more than 460,000 commercially licensed truck drivers resided in California in 2019 and only half of them are operating right now. The shortage might be due to many California truck drivers—especially those that worked as independent contractors at the ports—having either left the state or taken other jobs because of a 2020 state law requiring companies to classify independent contractors as employees, increasing the cost burden on an already stressed system. The law had ridesharing apps in its sights, but truckers were in the line of fire also, leaving many to move on to less restricted job opportunities. Because California is the entry point to well over a quarter of the U.S.’s imported goods, it’s regulations can have a ripple effect throughout the U.S. economy.

This challenge is not unique to the U.S. The Philippines have instituted a “no work, no pay” rule for their unvaccinated population. Canadian employers are responding to an expected government mandate by firing or putting on leave unvaccinated employees, even as they experience a tightening labor market. The U.S. has set a January 4 deadline for large employers to have their employees either fully vaccinated or tested on a weekly basis. In other words, the global labor shortage, amplified by mandates, is becoming an ongoing issue.

A very rough estimate is that unvaccinated adults make up about 20% of the U.S. labor force. A little over a third of the unvaccinated have responded to polls saying they will leave their jobs if their employer mandates a vaccine or weekly testing. We are not sure how this will end, but we can see the likely initial result is more scarcity in labor.

The shift to a more regulated environment reminds us of the philosopher Zeno’s dichotomy paradox, which argues that a person walking between two points must first walk halfway. And before they can walk halfway, they must first walk a quarter, and then an eighth, and then a sixteenth. Zeno extrapolates this to the point where a person must walk an infinite number of infinitesimal distances to get to the destination. And the one thing we know about infinity, it’s a long way away.

We bring this up not because the distance is impossible to complete, but because the rules put onto the mission, and the myopic perspective they encourage, produce what seems to be an impossible objective. We see something similar in our world today, with blunt laws, rules, and attitudes combining to artificially and illogically increase the distance to our objective, which in this case is reducing scarcity.

The likelihood that scarcity will continue, and inflation will remain higher for longer is becoming embedded into the fixed income markets. We mentioned in late summer the degradation we saw in the credit markets as Chinese property developers were experiencing rising rates of default. Credit markets have continued to deteriorate, overcoming the positive momentum in world equity markets. We have long highlighted investment markets lacking fundamental valuation support and, currently, we are adding the observation that credit markets are showing fatigue. We see it as a time to increase our level of conservativism. We have recently moved the portfolios to be a bit more cautious, raising cash levels to 20% across all strategies.

- We are firm believers that evolution towards better outcomes is a never-ending process yet over modern times, we have experienced innovation cycles where the advancement in cheaper, better, faster accelerates and decelerates. We think this graphic does a better job than we could at depicting the recent cycles in technological advancement. ↑