“If I can be optimistic when I’m nearly dead, surely the rest of you can handle a little inflation” – Charlie Munger, Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway (99 years old)

We’ve been saying for a while that today’s market landscape is shaping up to be quite different from the past. We said it first in our December 2021 newsletter, “No More Mr. NICE Guy.” We doubled down on the sentiment in June 2022, with “A New Regime.” Predicting shifts in the economy isn’t a walk in the park, especially because such forecasts span years, and it can also take years to verify their accuracy.

Although experts always have room to disagree, it’s reassuring when others with considerable expertise corroborate our outlook on the likely future market conditions. Specifically, we would like to bring your attention to two memos by Oaktree Capital Management’s Howard Marks, who, with more than five decades of investment experience, began arguing in December 2022 that we are likely in front of a materially different investment landscape as we exit the period of easy money across the globe. Although his “Further Thoughts on Sea Change,” from May, offers a comprehensive overview, we recommend also reading last December’s “Sea Change,” for a more nuanced understanding.

Two of Mark’s comments (in bold text throughout this newsletter) stood out to us.

“This memo’s main message is that the changes I described in Sea Change aren’t just usual cyclical fluctuations; rather, taken together, they represent a sweeping alteration of the investment environment, calling for significant capital reallocation.”

“Bottom line: If this really is a sea change—meaning the investment environment has been fundamentally altered—you shouldn’t assume the investment strategies that have served you best since 2009 will do so in the years ahead.”

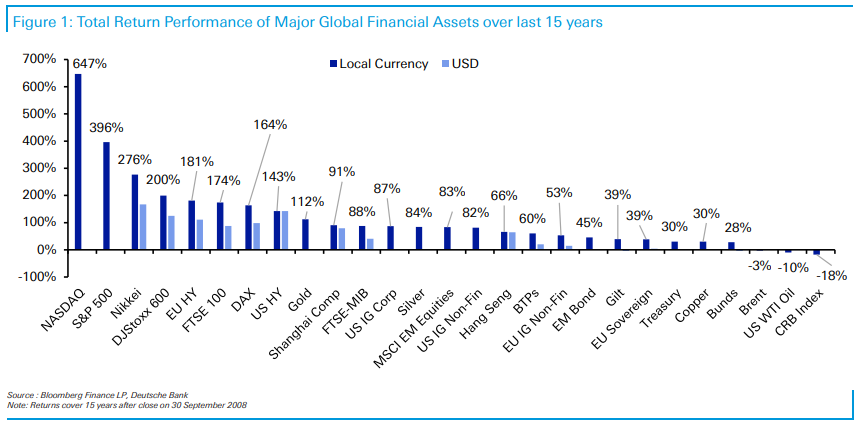

The chart above shows the total return of various segments of the global market since the market bottom of 2009. For many, this was the start of the easy money environment, when central banks began working to solidify the balance sheets of the global banks. Equities shined over the next 15 years, with the tech blockbusters found in the NASDAQ, leading the charge by a large margin. (It is not surprising that equities outperformed fixed income; equities were very depressed at the end of the financial crisis.) The NASDAQ outperforming is telling. With easier money flowing into the investment world, and with rates falling, investors looked to long-term growth opportunities, not fearing economic uncertainty as it became assumed that central banks would save us from a weakening economy.

Tighter monetary conditions could change the leaderboard, if Marks’ comment is accurate. Whom it changes to is uncertain, but it would be difficult to argue that high-growth companies will command the same valuations going forward.

Let’s move on to another thought Marks emphasizes:

“Everyone who has come into the business since 1980, in other words, the vast majority of today’s investors, has with relatively few exceptions only seen interest rates that were either declining or ultra-low (or both).”

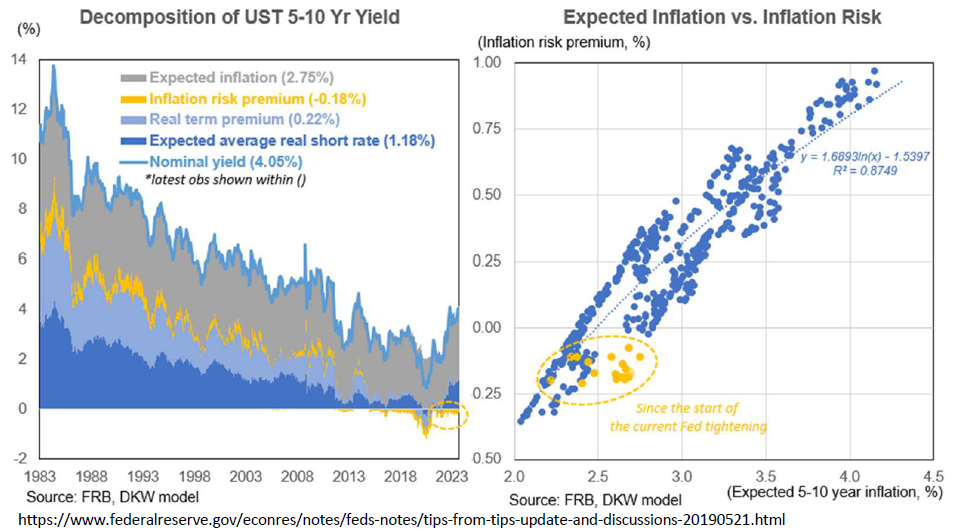

The left chart, above, shows intermediate government yields since 1983—note the ever lower interest rates until 2021—and attempts to decompose the interest rate into the primary factors that drive it. The other observations that stick out to us are the market’s continued belief in a future lower rate environment (expected average real short rates in dark blue), the belief that investors will not demand higher rates for longer-term debt (real term premium in light blue), and the negative expectation for inflation (inflation risk premium in yellow).

The chart on the right shows that the rising inflation expectations (shown in yellow) have not been reflected in a higher inflation risk premium as the dots lie under the historical trend. If we do not see inflation expectations move lower, the tendency would be for long-term rates to build in a more normal premium that could result in another 1% move higher in rates for that component alone. We could see how the charts displayed above lead to the following comments from Marks:

“In Sea Change, I listed several reasons why I don’t think interest rates are going back to that period’s lows on a permanent basis, and I still find these arguments compelling. In particular, I find it hard to believe the Fed doesn’t think it erred by sticking with ultra-low interest rates for so long.”

“Rather than letting economic and market factors determine the rate of interest, the Fed has been unusually active in setting interest rates, greatly influencing the economy and the markets.”

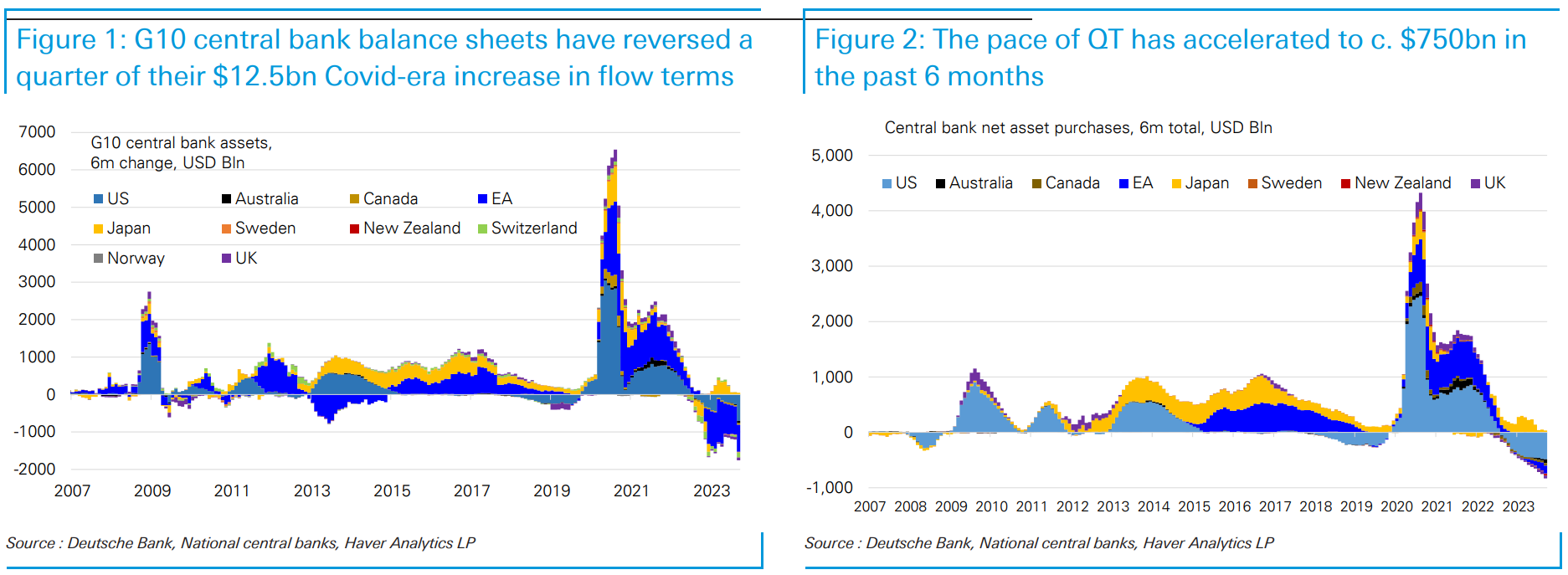

The charts below help demonstrate Marks’ statement about central banks setting interest rates. Since the financial crisis, central banks have been buying government debt in their effort to lower interest rates. That behavior accelerated during the Covid response, significantly distorting global market pricing and likely leading to malinvestment. He says:

“Importantly, this distorts the behavior of economic and market participants. It causes things to be built that otherwise wouldn’t have been built, investments to be made that otherwise wouldn’t have been made, and risks to be borne that otherwise wouldn’t have been accepted.”

If it is true we are moving into a new regime of tighter money—as would be expected from the charts above, which suggest a draining of liquidity through quantitative tightening—it should be expected that the distorted investing and risk-taking will unwind. The issue is that we are not sure how it would happen.

Marks lays out a convincing argument for a change in regime—the sea change—but one should question if his specialty, which is opportunistically purchasing distressed debt instruments, biases his view. He acknowledges this, addressing the ways he could be wrong. One stands out:

“If inflation isn’t brought under control, nominal returns could lose significant value when they’re converted into real returns, which are what some investors care about most.”

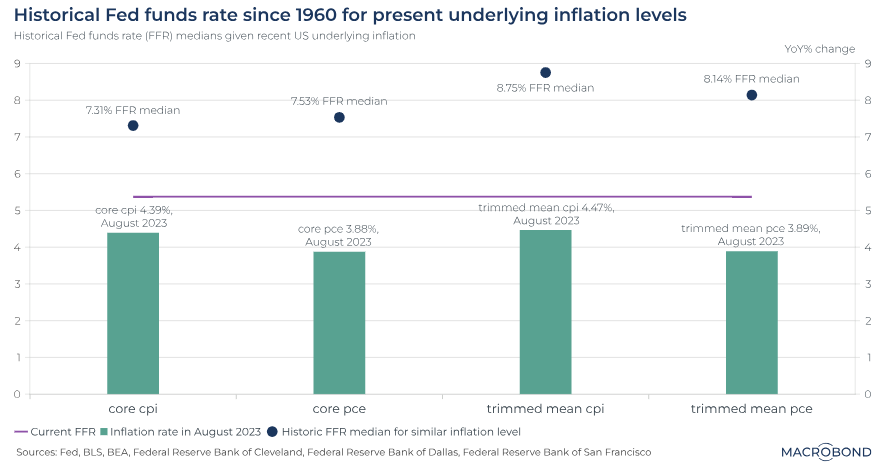

And back we come to that dreaded inflation conversation. Historically, current inflation readings would have had us at much higher short-term rates, as depicted in the chart below. Using various forms of inflation (shown in the green columns), historical rates would be between 7% and 9%, versus the current level of 5.75%.

And back we come to that dreaded inflation conversation. Historically, current inflation readings would have had us at much higher short-term rates, as depicted in the chart below. Using various forms of inflation (shown in the green columns), historical rates would be between 7% and 9%, versus the current level of 5.75%.

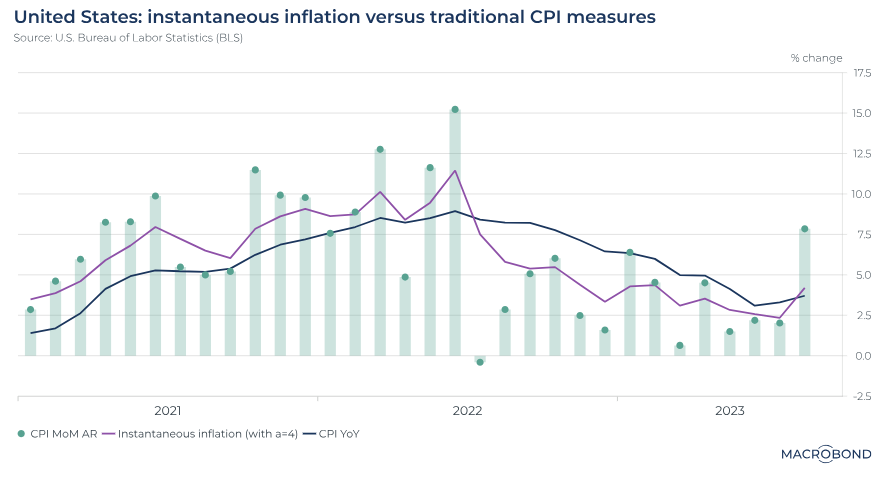

To make matters a bit worse, the deceleration in inflation readings we have experienced since the beginning of the year has lessened. And we could start to see inflation tick back up. The chart below looks at those elements within the inflation calculation that are faster to adjust. Recent readings are signaling a move higher rather than a continuation lower.

To make matters a bit worse, the deceleration in inflation readings we have experienced since the beginning of the year has lessened. And we could start to see inflation tick back up. The chart below looks at those elements within the inflation calculation that are faster to adjust. Recent readings are signaling a move higher rather than a continuation lower.

This all sounds scary, but it could be looked at more as returning to a period that we experienced in the past, specifically the late 60s and throughout the 70s. Therefore, if Marks is right, we should be learning from the past and trying to avoid the market segments that were more recently benefiting from the easy money. As Charlie Munger said, “All I want to know is where I’m going to die so I never go there.”

Where are those places that potentially require avoidance or at least caution? We will answer with a few comments made by Marks in his May 2023 newsletter:

“Five years ago, an investor went to the bank for a loan, and the banker said, ‘We’ll give you $800 million at 5%.’ Now the loan has to be refinanced, and the banker says, ‘We’ll give you $500 million at 8%.’ That means the investor’s cost of capital is up, his net return on the investment is down (or negative), and he has a $300 million hole to fill.”

We see this as a bigger issue in 2024, when about a third of the high-yield debt market will reach their maturity dates and need to refinance. Many took advantage of the low rates after Covid and will now need to right size their business for a new environment.

“It’s very notable that almost the entire history of levered investment strategies has been written during a period of declining and/or ultra-low interest rates. For example, I would venture that nearly 100% of capital for private equity investing has been put to work since interest rates began their downward move in 1980. Should it come as a surprise that levered investing thrived in such salutary conditions?

The private equity market is estimated to be $4.7 trillion by Preqin, a research group focused on alternative investing, about ten times larger than it was in 2000. As Marks suggests, we doubt many of the current participants in the private equity market have gone through an extended period of rising rates and tight money. Goldman Sachs estimates that over half the experienced return in private equity funds has come from multiple expansion and leverage—two factors that may turn tailwinds into headwinds for the industry. Marks says,

“Whatever the intrinsic merits of asset ownership and levered investment, one would think the benefit will be reduced in the years ahead. And merely riding positive trends by buying and levering may no longer be sufficient to produce success. In the new environment, earning exceptional returns will likely once again require skill in making bargain purchases and, in control strategies, adding value to the assets owned.”

The last 15 years have been a panacea for momentum-leaning investors. And if you could invest while using leverage, your dreams could come true. Now, that may change. What made people rich through high levels of leverage might lead to ruin. Value-based investing has had a tough time through this easy money period. That may change in the new regime.

“Finally, conditions in those halcyon days [of low interest rates] created tough times for bargain hunters. Where do the greatest bargains come from? The answer: the desperation of panicked holders. When times are troubled, asset owners are complacent, and buyers are eager, no one has any urgency to exit, making it very hard to score significant bargains.”

If Marks is right, and we are heading into a period where central banks cannot or will not backstop the investment markets, bargains will start to show themselves. Our mantra has always been what Warren Buffett said best, investors are wise “to be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful.”

The reference window for many may span a decade or so. In that case, the overarching assumption that the current high level of interest rates is transitory and will soon revert to their low levels that some investors consider more ‘normal.’ However, interest rate cycles have historically covered 60 – 70 years, making the last 15 years only a phase within the cycle. We concur with Marks that now is the time to expand one’s view to a longer time period and prepare for a different investment landscape.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

This report is for informational purposes only and does not constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any securities mentioned herein. This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. All of the recommendations and assumptions included in this presentation are based upon current market conditions as of the date of this presentation and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk including the loss of principal.

All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Information contained in this report has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, Auour Investments LLC makes no representation as to its accuracy or completeness, except with respect to the Disclosure Section of the report. Any opinions expressed herein reflect our judgment as of the date of the materials and are subject to change without notice. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors and are not intended as recommendations of particular securities, financial instruments or strategies to particular clients. Investors must make their own investment decisions based on their financial situations and investment objectives.