From The Perfect Storm

Our investment objective is to produce above-market, risk-adjusted returns—over an investment cycle—at a lower level of experienced risk while mitigating the declines our clients experience over that investment cycle. Over the course of nine years, we have—to date—achieved it. [Past performance does not guarantee future returns.]

Our method is to detect changing risk environments that, based on historical experience, have led to a higher chance of a market downturn. If we are good at this, we can then reposition the portfolio into a defensive position (likely to include holding high levels of cash, a.k.a. dry powder), limiting the pain and allowing for reinvestment later at better prices. That is our aim, not a promise.

Long-term investing is like setting out to sail across the ocean, heading for a destination on the opposite coast. You plan to catch the Westerlies and traverse the Atlantic from west to east. All you need to do is set the sails, grab the wind and be off! Not quite. Storms present themselves throughout the journey, and each time you must choose the path: through the eye of the storm or detour around it. Most investors are told to weather the storm and hope for the best. At Auour, we choose to go around it. You never know how bad it can get; sometimes storms cause shipwrecks.

We started to move around an expected storm a little over one year ago, beginning in December 2021. During the first half of 2022, we turned a bit more away from the storm by raising cash levels in portfolios. In October 2022, we turned back towards the storm, seeing an opportunity. However, that does not assume that we are past the storm completely. Data suggests we might be in a lingering storm that requires further respect and attention as we thread in and out of the storm’s perimeter. We might need patience as we work our way around it. And, of course, it might not be like past storms. (History doesn’t repeat itself so much as it rhymes.)

The last three decades have trained investors to be impatient as market declines were met with accommodative central banks and enhanced government spending. Starting with the Asian currency crisis of 1997, then the turning of the clock to the new millennium, then the Global Financial Crisis, and ending with the pandemic, global authorities in charge of societies’ collective purses have responded with easy money and fiscal stimulus to dampen the pain felt by consumers and investors alike. A typical economic backdrop to those past calamities was a tame inflationary environment, allowing money printing to produce the desired effect without causing (at least noticeably causing) an overheating of the economy.

A current concern is that today’s environment could play out differently than in the past two decades. Inflation seems uncomfortably high to the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank, the global provider of dollars. And rather than the Fed coming to the aid of an economic problem, they are now causing it because they see excess demand as the inflationary culprit. Stating it differently, central banks came in during past economic slowdowns to spur demand through easy money. Now? They aim to shrink demand by draining money from the system if they think inflation stays uncomfortably high.

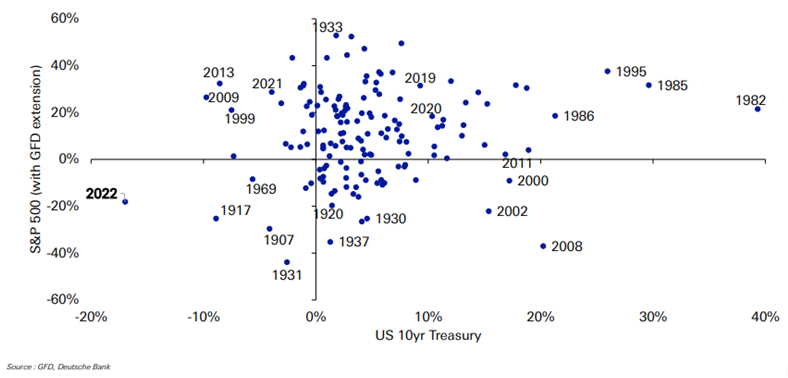

We do not want to spend much time revisiting 2022, apart from sharing the above chart that painfully sums up the year in context, showing the annual returns for equities and fixed income indices by calendar year. 2022 was a horrible year with little resemblance to past experiences. It was a perfect storm in which elevated valuations, overconfidence in growth, and cheap money collided.

As we look to the rest of 2023 and beyond, we highlight a few important questions for understanding the path forward and the potential lingering impacts of the current storm.

- Did the response to the pandemic by central banks mitigate the importance of yield-curve monitoring?

- Is CEO sentiment an important indicator for labor markets and economic activity?

- Is the inflation we are experiencing controllable with neutral interest rates?

- Is there a structural element to inflation that has yet to be discussed or addressed?

- Can global economies move back to an easy money environment that existed for the past two decades, or do we need to adjust to a more expensive and tighter monetary system?

- Does history repeat with the next bull market having a new leader? If so, what should we be looking at?

- Will the conversations decisively turn to corporate earnings from inflation?

Let’s take each one individually.

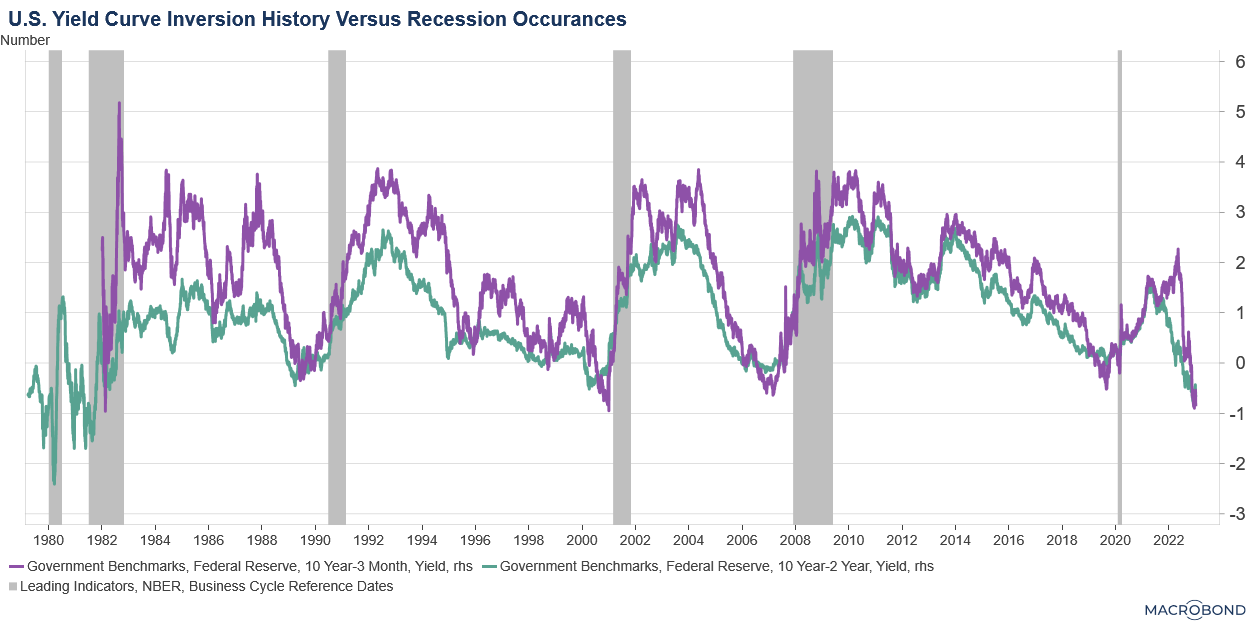

1. Did the response to the pandemic by central banks mitigate the importance of yield-curve monitoring?

Economic activity benefits from a financial system that borrows in the short term and invests long term. However, economic activity has historically stumbled when short-term rates rise above long-term rates, which is to say, when the yield curve is inverted. The chart below shows that yield curve inversion occurred somewhat reliably before a recession.

Economic activity benefits from a financial system that borrows in the short term and invests long term. However, economic activity has historically stumbled when short-term rates rise above long-term rates, which is to say, when the yield curve is inverted. The chart below shows that yield curve inversion occurred somewhat reliably before a recession.

The time between when inversion occurs and when a recession (in hindsight) starts has varied considerably throughout history. In some cases, it was as short a period as six months. In other cases, it took multiple years. On average, it has been about 18 months. The yield curve inverted in the summer of 2022, suggesting a recession starting mid to late 2023. Some argue that it could begin sooner, given the aggressive rate increases we have experienced as we came off the zero bound. Others suggest that moving from a zero-rate level neutralizes the importance of inversion, which, from our perspective, is a this-time-is-different argument. Given the historical significance of this signal, we stand closer to believing that no matter why it happened, the fact that the yield curve did invert is an important signal.

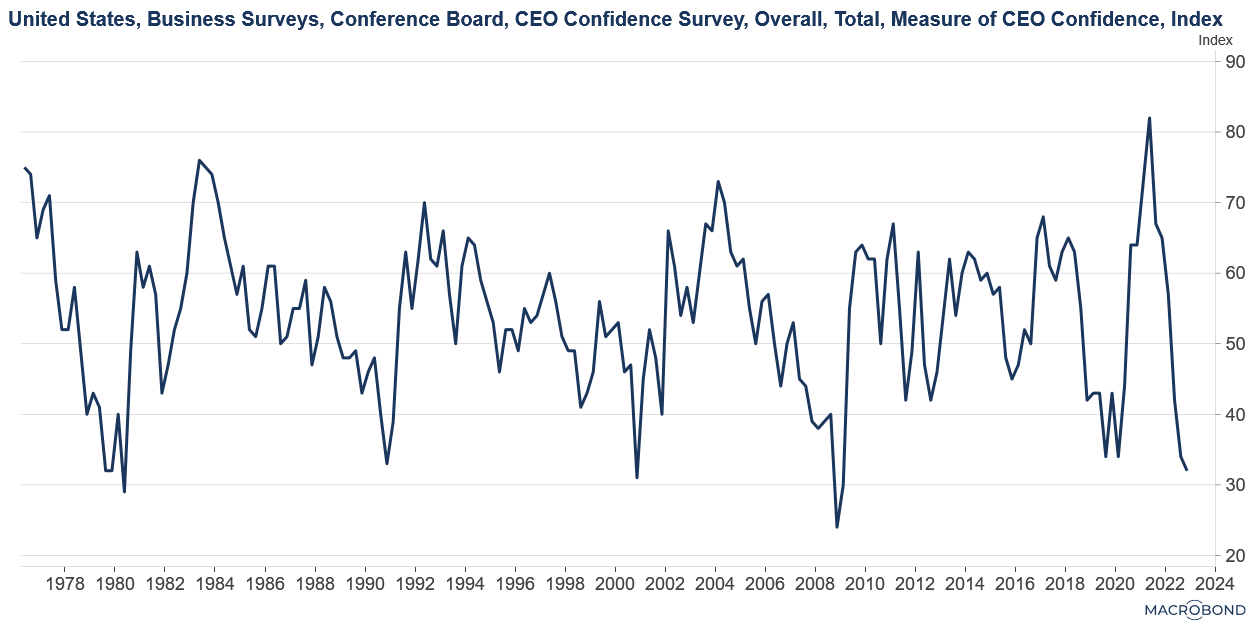

2. Is CEO sentiment an important indicator for labor markets and economic activity?

As of this writing, CEOs are not showing confidence. Recent survey results are near the worst experienced. Past periods of lack-of-confidence have led to or coincided with softening labor markets and periods of slow or negative growth. In addition, leading companies within the technology sector have been making headlines with their notable layoffs. It should be mentioned that the confidence of CEOs is volatile and came off extreme exuberance in late 2021. Are the current negative feelings driven by a reflexive move from past exuberance, or is something more amiss? It is important to watch this metric for clues on the  severity of any labor market correction.

severity of any labor market correction.

3. Is the inflation we are experiencing controllable with neutral interest rates?

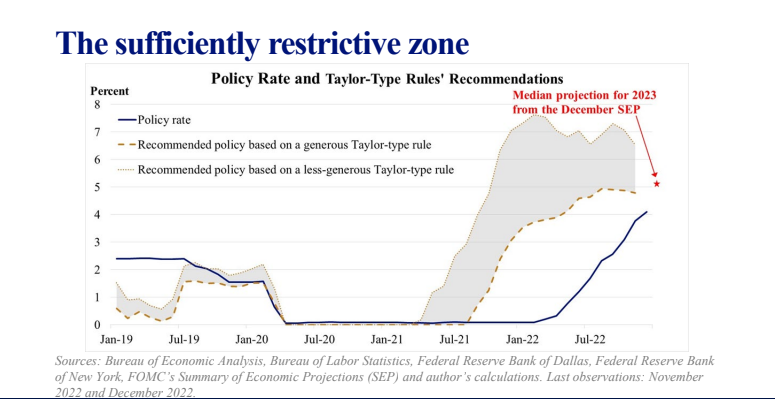

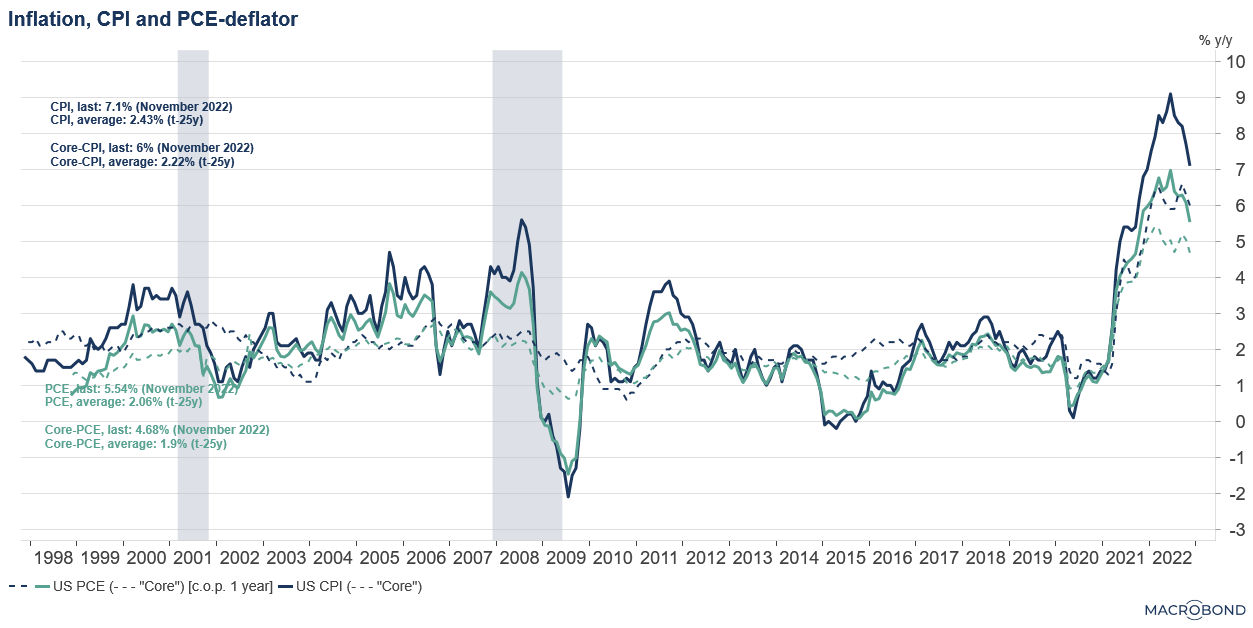

Discussions fill the airwaves about how much is enough concerning interest rate hikes. Coming from a long period of zero, it is understandable that even 4% seems large and restrictive. And in some cases, it may be (think private equity, commercial real estate, and home prices). However, there is ample reason to believe we are not yet at a point where rates can contain inflation. In December, Fed officials communicated to investors that rates might need to move as high as 5 to 7% under some measures. If true, assets purchased with cheap debt at high prices over the past ten years will likely experience trouble. During past debt work-off periods, we saw owners giving the property’s keys to the banks. We have only seen one example of this so far. We are watching to see additional evidence of this.

Discussions fill the airwaves about how much is enough concerning interest rate hikes. Coming from a long period of zero, it is understandable that even 4% seems large and restrictive. And in some cases, it may be (think private equity, commercial real estate, and home prices). However, there is ample reason to believe we are not yet at a point where rates can contain inflation. In December, Fed officials communicated to investors that rates might need to move as high as 5 to 7% under some measures. If true, assets purchased with cheap debt at high prices over the past ten years will likely experience trouble. During past debt work-off periods, we saw owners giving the property’s keys to the banks. We have only seen one example of this so far. We are watching to see additional evidence of this.

4. Is there a structural element to inflation that has yet to be discussed or addressed?

The mania for “faster, better, cheaper” has dominated hype in economic cycles over the last 40 years as technology has embedded itself within our lives. Deflationary trends also helped, as manufacturers took advantage of lower-wage geographies. However, we may be seeing deflationary tailwinds turning into inflationary headwinds.

The mania for “faster, better, cheaper” has dominated hype in economic cycles over the last 40 years as technology has embedded itself within our lives. Deflationary trends also helped, as manufacturers took advantage of lower-wage geographies. However, we may be seeing deflationary tailwinds turning into inflationary headwinds.

The global community is changing the “faster, cheaper, better” mantra to “faster, cheaper, better, less harmful.” Concerns that we humans are harming the environment are taking center stage as concerns also grow about the exploitation of slave labor within regions of China. Add to that the growing skepticism around supply dependency on China, and one can see significant investment is being diverted to changing the manufacturing of current output. These significant investments are not expected to bring about lower-cost products or added demand—in many cases, the products cost more.

5. Can global economies move back to an easy money environment that has existed for the past two decades, or do we need to adjust to a more expensive and tighter monetary system?

5. Can global economies move back to an easy money environment that has existed for the past two decades, or do we need to adjust to a more expensive and tighter monetary system?

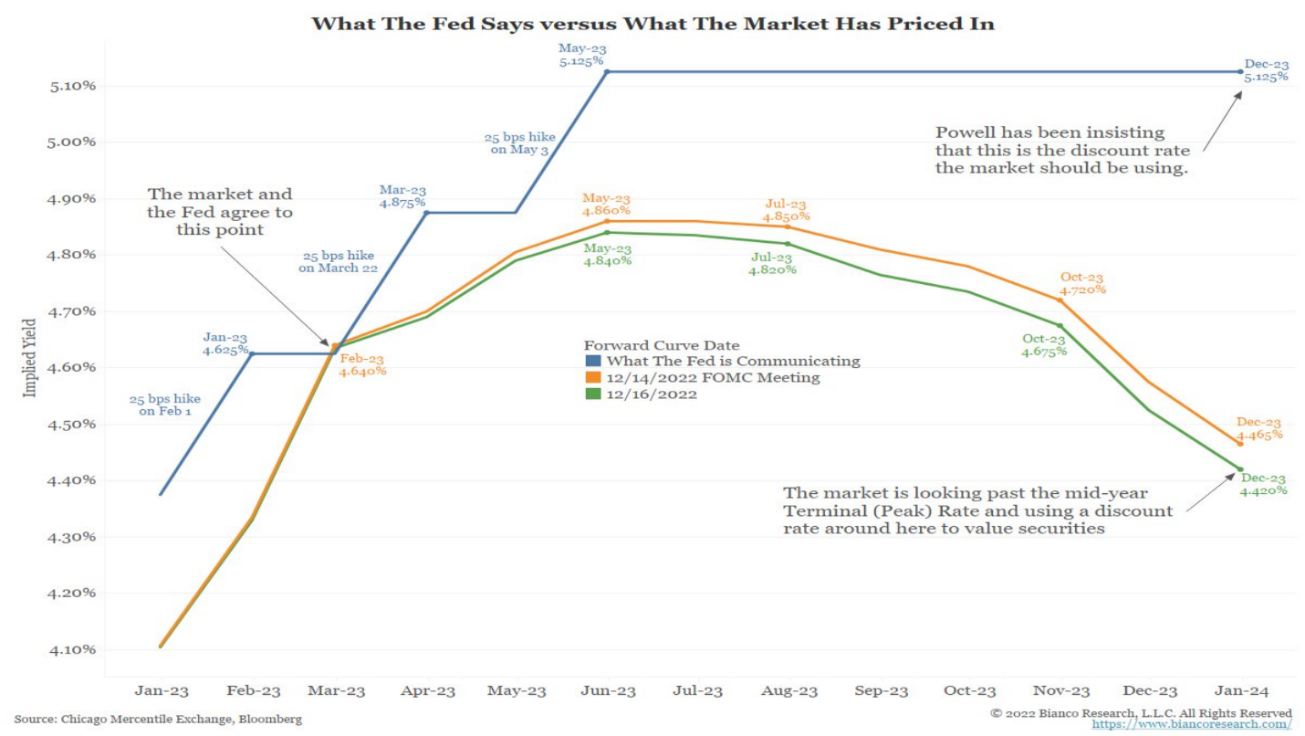

There is a large discrepancy between the Fed’s view of the future cost of money and what investors think. The chart above highlights the expectations of the Fed on future interest rates (blue) and investors’ expectations (green and orange).

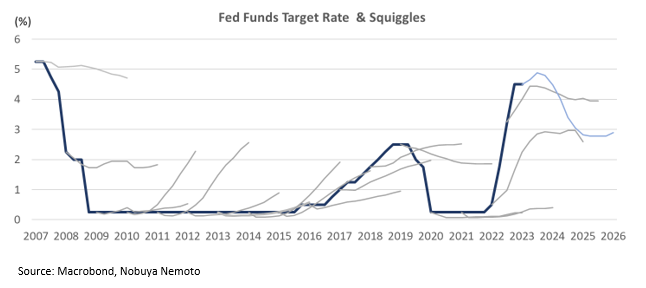

Who is right? If the past is to be respected, neither. Both players have exhibited severe anchor bias—thinking rates will rise back to recent past experiences or fall to recent past experiences depending on the mid-term trajectory. Both have shown little predictive capabilities, as shown in the chart below. The blue line shows the historical Fed Funds rate, while the gray lines depict the future expectations of the rate at that time. There has been a strong bias toward believing that rates go back to where they came from in a relatively short period. And history suggests that bias is nearly always wrong.

Who is right? If the past is to be respected, neither. Both players have exhibited severe anchor bias—thinking rates will rise back to recent past experiences or fall to recent past experiences depending on the mid-term trajectory. Both have shown little predictive capabilities, as shown in the chart below. The blue line shows the historical Fed Funds rate, while the gray lines depict the future expectations of the rate at that time. There has been a strong bias toward believing that rates go back to where they came from in a relatively short period. And history suggests that bias is nearly always wrong.

We don’t have a strong opinion (we have an opinion, just not a strong one) other than wanting to respect the fight between the two rate makers at present. We see the discrepancy bringing about high levels of uncertainty. Asset prices are very dependent on interest rates. With the current disparity in rate expectations, one should assume asset pricing will be more volatile than average.

6. Does history repeat with the next bull market having a new leader? If so, what should we be looking at?

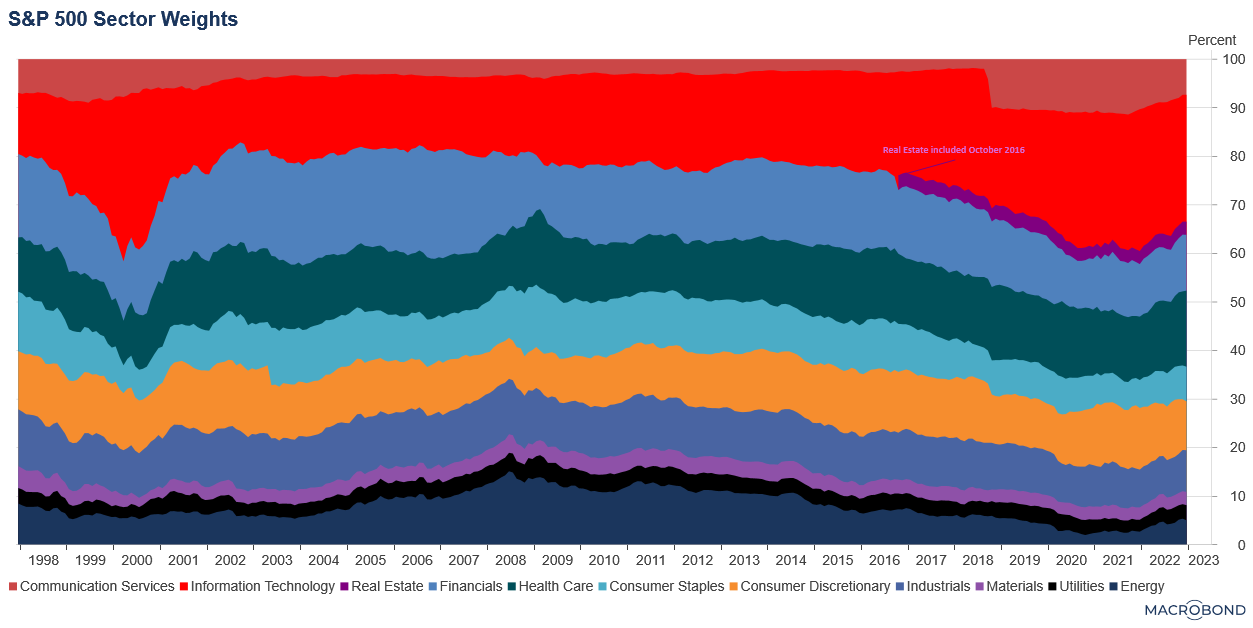

Historical market recoveries from bear markets have been consistent in that the leader of the past bull market always lags within the new bull market. For example, the technology sector led in the bull market that ended in 2000, and it then lagged as the energy and financial sectors reaped the rewards of the next bull market. The last decade of market gains again showed technology companies being favored, with the sector’s weight within the S&P500 index reaching almost the same magnitude as in 2000.

Is it different this time, where we see the dominant technology companies recover and lead the markets into a new growth phase? Again, the lessons from history take much work to fight. If it is true that heavy investment is needed to move away from China, technology may be the one sector that carries the heaviest of loads.

Is it different this time, where we see the dominant technology companies recover and lead the markets into a new growth phase? Again, the lessons from history take much work to fight. If it is true that heavy investment is needed to move away from China, technology may be the one sector that carries the heaviest of loads.

7. Will the conversations turn decisively to corporate earnings from inflation?

Much of the financial discussion today revolves around inflation, and this newsletter is no different. It begs the question, are we looking in the wrong direction? Not really. Many are focused on if and/or when a recession comes about to help predict the future of corporate profits, which are a material driver of stock prices.

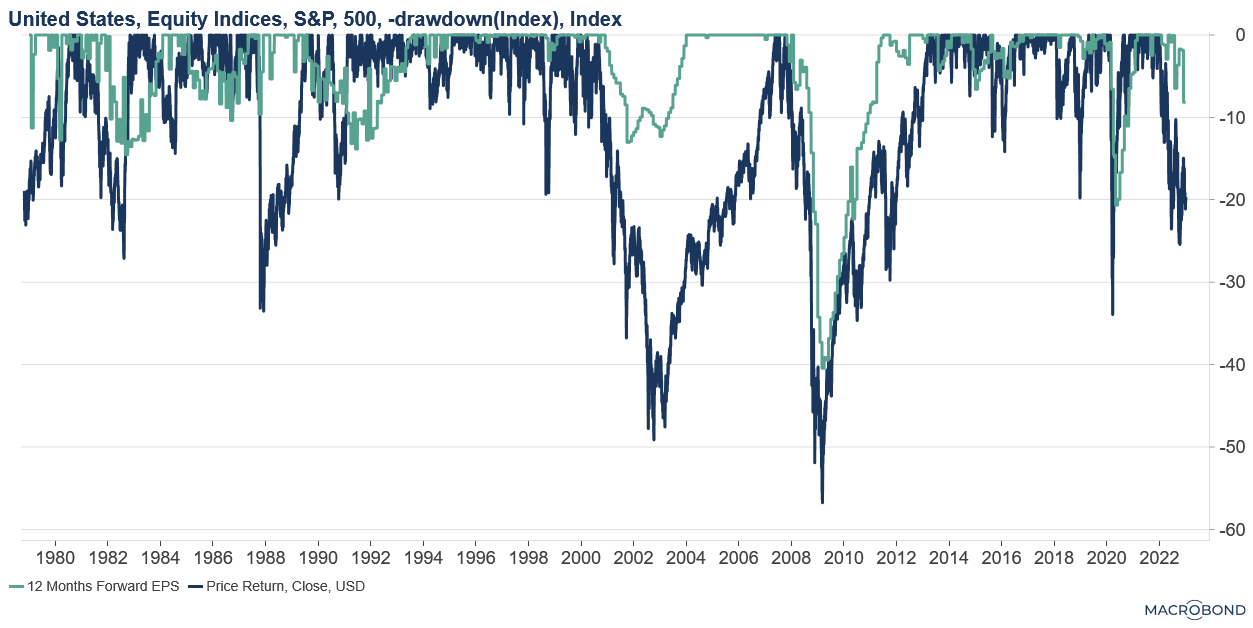

The chart below looks at the declines from peaks for stock prices (as measured by the S&P 500 index) in blue and the decline in corporate earnings from peaks in green. As expected, as earnings decline, asset prices decline. Past economic weakness shows a varying level of earnings decline, with the recession of the early 2000s showing a 13% decline from peaks while the Great Financial Crisis took earnings down 40%. Today, expected earnings are off about 8% from the earnings experienced in 2022, a moderate decline relative to history. To us, it appears analysts and company executives expect a very modest soft-landing scenario.

The chart below looks at the declines from peaks for stock prices (as measured by the S&P 500 index) in blue and the decline in corporate earnings from peaks in green. As expected, as earnings decline, asset prices decline. Past economic weakness shows a varying level of earnings decline, with the recession of the early 2000s showing a 13% decline from peaks while the Great Financial Crisis took earnings down 40%. Today, expected earnings are off about 8% from the earnings experienced in 2022, a moderate decline relative to history. To us, it appears analysts and company executives expect a very modest soft-landing scenario.

Inflation is the problem, and the Fed thinks a recession is probably the answer. Investors around the globe are accustomed to central banks dissipating economic softness. This time, the central banks are guiding the eye of the storm directly at the economy as they fight inflation.

Recessions are normal, even if painful. We believe we are in the bottoming process right now. The good news is that health in the labor market is likely to soften the blow, so maybe we will see a reset in growth expectations rather than a reset in operating norms. But even soft landings have a thump.